The Quirks of C printf Parameter Handling on macOS: What Happens When printf Uses %d to Print a Floating-Point Number?

This morning while browsing the web, I came across a 2016 article that mentioned this piece of code:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

double a = 10;

printf("a = %d\n", a);

return 0;

}

It stated that when this code runs on x86 (IA-32) architecture, the output is 0; on x86-64, the output is a different random number every time.

I tested it, and sure enough, that’s exactly what happened:

zhonguncle@ZhongUncle-Mac-mini test % ./a.out

a = -1194089144

zhonguncle@ZhongUncle-Mac-mini test % ./a.out

a = -1094355640

I was extremely curious about why this happens. The 0 on 32-bit systems is easy to understand, but why do we get random numbers on 64-bit systems?

You can probably make a rough guess—it’s related to memory addresses (weird random numbers almost always point to address issues, like “reading from the wrong memory location”). But blind guesses are prone to mistakes, so verification is necessary. First, I checked if anyone had researched this online.

Later, I found out that the original version of this problem dates back nearly 20 years. However, since most machines were 32-bit back then, the issue was manageable. Around 2008, as 64-bit machines became popular, the problem evolved to include the 64-bit behavior described above.

In the early years, China’s tech industry was still developing, and Microsoft had significant influence at the time. As a result, most research blogs and records in China focused on Windows, with many excellent resources that I’ve included in the “References/Further Reading” section at the end—feel free to check them out if you’re interested.

Abroad, there are discussions about macOS and Linux, but they are not as in-depth. Since I couldn’t find the exact information I needed, I decided to investigate it myself.

This article uses an Intel-based Mac for explanation. The reason on Linux is similar, and essentially the same as Windows, though with minor differences.

Why x86-32 Returns 0 (IA-32)

IA-32 architecture is the instruction set architecture and programming environment for Intel’s 32-bit microprocessors.

When printf uses %d, it fetches 2 bytes from the corresponding position in the stack memory.

This makes the 32-bit behavior easy to understand: on 32-bit systems, int is typically 2 bytes, double is 4 bytes, and the machine’s registers are at most 32 bits wide.

The hexadecimal representation of the floating-point number 10 is 00 00 24 40, so it is pushed onto the stack in the order 40-24-00-00, with 00 at the top of the stack. When printf retrieves the value for %d, it pops 2 bytes (4 hexadecimal digits) from the stack—00-00, which equals 0.

If you output using the following code:

double a = 10;

printf("%d %d", a, a);

You’ll find the second output is no longer 0. This is because there is still one value left in the stack, which is 10.

macOS no longer supports 32-bit systems, but similar behavior occurs on 64-bit systems—this is not simply an overflow issue.

How printf Works

Before diving into the 64-bit problem, we need to understand how printf works. The specific cause of this issue is tied to printf’s implementation (as you saw, it’s also related to the 32-bit case, but we didn’t need to delve into it deeply).

For Linux and macOS, you can view the library function manual with man 3 printf, and you’ll find this statement about its structure:

In short: the function is implemented with a format string and the stdarg library functions.

The stdarg manual includes an example at the end that implements a simplified version of printf (reading manuals pays off!):

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdarg.h>

void foo(char *fmt, ...) {

va_list ap, ap2;

int d;

char c, *s;

va_start(ap, fmt);

va_copy(ap2, ap);

while (*fmt) {

switch (*fmt++) {

case 's': // string

s = va_arg(ap, char *);

printf("string %s\n", s);

break;

case 'd': // int

d = va_arg(ap, int);

printf("int %d\n", d);

break;

case 'c': // char

c = va_arg(ap, int);

printf("char %c\n", c);

break;

}

}

va_end(ap);

while (*fmt) {

switch (*fmt++) {

case 's':

s = va_arg(ap2, char *);

break;

case 'd':

d = va_arg(ap2, int);

break;

case 'c':

c = va_arg(ap2, int);

break;

}

}

va_end(ap2);

}

int main() {

double a=10;

foo("sdc", "Today", a, 'C');

return 0;

}

Here, foo() is our custom implementation of printf. In foo("sdc", "Today", a, 'C');, the first parameter "sdc" is the format string: "Today" corresponds to s (string), and the subsequent arguments map to the remaining specifiers.

We care about the types and their corresponding values, so the output is:

string Today

int 10

char C

As you can see, the values and their order are determined by the format string.

Implementing this helps us understand how printf operates. The program above increments through the format string, matches the appropriate arguments, and prints them.

The format string in the real printf is much more complex, but the core idea is the same: push the remaining arguments onto the stack from right to left, then pop them from the stack to match the format string specifiers.

This is exactly how printf works. We can use this similar implementation to experiment and find the root cause!

I couldn’t debug the system printf with LLDB or other tools, but I could certainly debug my own code.

Notice in the code: the second parameter of va_arg(ap2, int); determines the argument type. This means passing a value of a different format will result in undefined behavior (since we didn’t write any validation logic).

What exactly happens? Let’s test it:

Change the integer to a floating-point number:

foo("sdc", "Today", 1.2, 'C');

Output:

string Today

int 67

char X

Testing with any floating-point number consistently yields int 67 char X.

Is this overflow? Let’s try a very large integer:

foo("sdc", "Today", 11231121212132, 'C');

Output:

string Today

int -218266908

char C

Even with integer overflow, char C remains unchanged. This means floating-point overflow may affect data outside the expected range, while integer overflow does not.

This behavior is caused by va_arg: the first parameter is the variable argument list, and the second specifies the type (i.e., how to process the variables). In the code above, we specified int—let’s change it to double:

case 'd': // int

d = va_arg(ap, double);

printf("%x\n",ap);

printf("int %d\n", d);

printf("%p\n",ap);

break;

Surprisingly, the output is correct:

string Today

int 10

char C

The manual states: if there is no next argument, or the type does not match the next argument (after promotion), random errors will occur:

Sure enough—this is the culprit, and the behavior matches exactly.

“Promotion” refers to converting a type to a larger range before processing, then converting it back. For example, a 64-bit float is first promoted to double, and an int is treated as an unsigned integer before processing.

64-bit Architecture

Intel® 64 architecture is the instruction set architecture and programming environment which is the superset of Intel’s 32-bit and 64-bit architectures. It is compatible with the IA-32 architecture.

Now let’s tackle the real question: why do we get random numbers on 64-bit systems?

Let’s modify the code slightly:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

double a = 10;

int b = 20;

printf("%d %d\n", a, b);

return 0;

}

Guess what the output is?

Here it is:

20 -1133869736

I didn’t reverse them—this is the actual output (only on Mac; Linux behaves differently). Why is the value of b printed first?

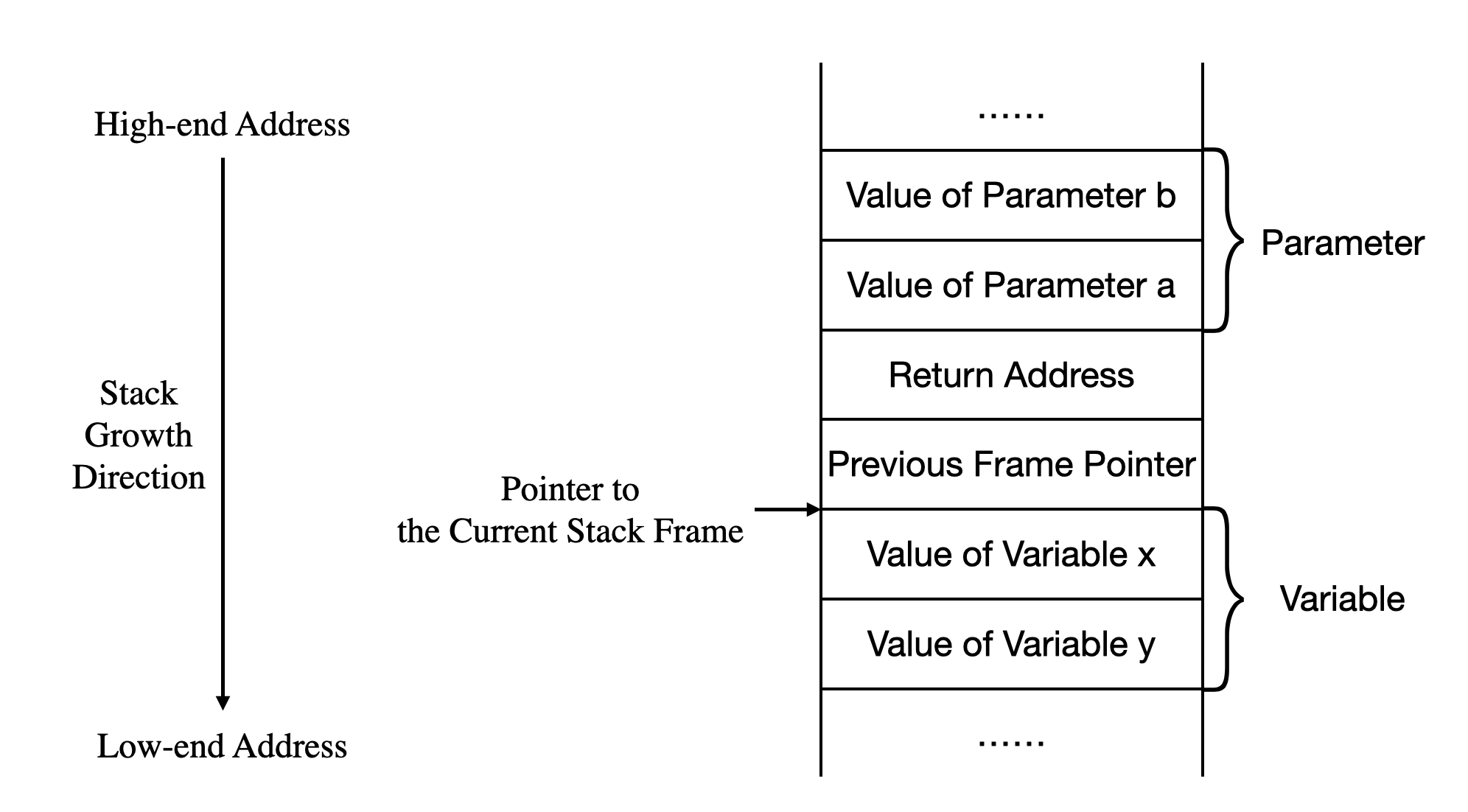

To understand this, you need to know the program’s memory layout (you could have skipped this in the previous section, but it’s essential here). The memory layout of a running program looks roughly like this:

Local variables are stored in the stack region when declared.

So the variables are ordered from high to low addresses as a and b.

This is also related to function calls: calling a function creates a frame on the stack to store the return address, arguments, and local variables. This includes the main function frame.

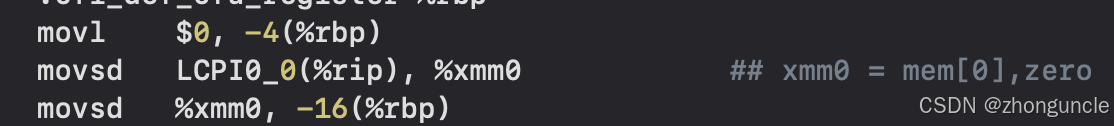

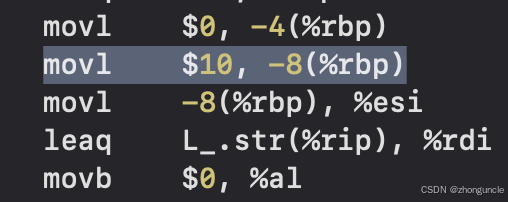

Important note: the stack grows from high addresses to low addresses, which is why assembly code uses subtraction:

subq $16, %rsp

movl $0, -4(%rbp)

movl $10, -8(%rbp)

movl -8(%rbp), %esi

leaq L_.str(%rip), %rdi

movb $0, %al

callq _printf

x86-64 is more complex: 32-bit registers and memory sizes are similar, making processing, conversion, and movement relatively straightforward. For early 16-bit data, 32-bit registers could be split into two parts to store two 16-bit values each.

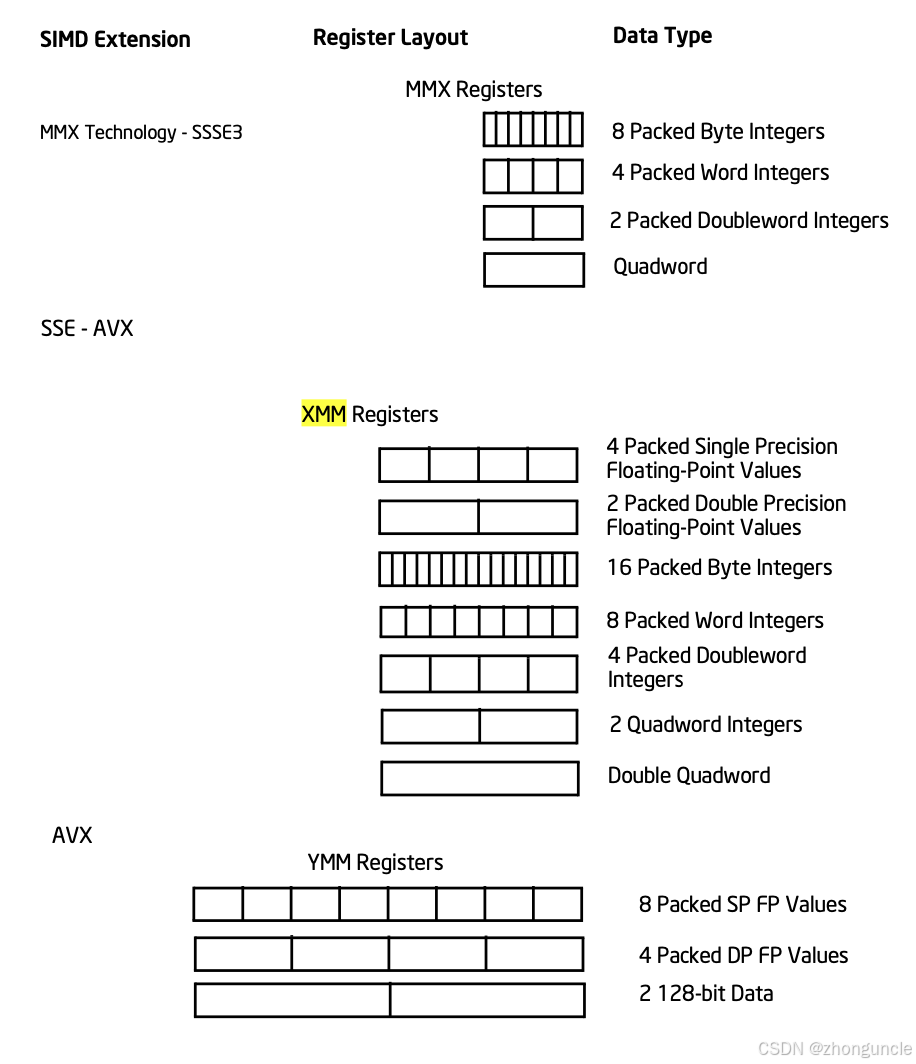

Intel later introduced MMX (for integers), adding 64-bit XMM registers to x86 CPUs. This was followed by the SSE (floating-point) instruction set series, expanding XMM registers to 128 bits. Modern AVX series features add even more, with YMM and ZMM registers (up to 512 bits). These instruction sets are primarily used for SIMD parallel computing (GPU is another implementation of SIMD).

On devices with YMM registers, the lower 128 bits of YMM are XMM.

SIMD enables the same computation on multiple pairs of data with a single instruction (instead of one instruction per pair), drastically improving performance. As a result, XMM and YMM registers can be split into multiple blocks:

The Clang compiler directly stores floating-point numbers in XMM registers when declared:

The comment indicates it’s stored in the xmm0 register: the front part is the storage location, and the rest are all 0s.

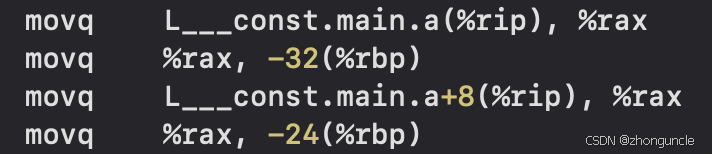

In contrast, floating-point arrays are first stored in memory (likely to facilitate parallel computing on multiple arrays):

For comparison, a single integer int doesn’t even need to be stored in memory—it’s passed directly as a value:

After research, I found this behavior is related to how printf retrieves arguments. You also need to understand the format differences between floating-point numbers and integers.

When printf pushes arguments onto the stack, the frame pointer register (EBP) and stack pointer register (ESP) point to the bottom and top of the current frame, respectively.

Let’s write a function to get the value of EBP:

void printEBP(){

unsigned long ebp;

asm("mov %%rbp, %0" : "=r" (ebp));

printf("EBP: %lx\n", ebp);

}

Whether you use this in our custom printf (must be used inside the function, not before/after—otherwise the frame is different) or the initial example, you’ll observe the following:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

double a = 10;

printf(" %p\n", (void*)&a);

unsigned long ebp;

asm("mov %%rbp, %0" : "=r" (ebp));

printf("EBP: %lx\n", ebp);

return 0;

}

Output:

0x7ff7bfeff310

EBP: 7ff7bfeff320

You’ll notice the random number matches the address stored in EBP except for the last two digits. The variable a is located just below the previous frame pointer (the address pointed to by the EBP register):

It’s important to emphasize that the order of local variables and the actual size of their regions are determined by the compiler—you should not assume their exact positions, but the overall structure remains consistent. Many compilers randomize stack addresses to prevent buffer overflow attacks (e.g., adding an extra pointer in the stack that points to the actual location). For example, the address may fall outside the frame range:

EBP: 7ff7bfeff320

0x7ff84f1e86c0

ESP: 7ff7bfeff300

This explains why you might get the same result multiple times—especially when running in Xcode (which may fix memory addresses temporarily to avoid issues), the address may not change at all with repeated runs in a short time. However, this does not mean it will always be the same.

The situation is now complex: we don’t know where the compiler ultimately stores local variables or how it processes them. Let’s assume we can find the actual location and focus on this scenario.

You can use a pointer to get the address of a, then retrieve its value—you’ll find the behavior is identical to the 32-bit case:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

double a = 10;

printf(" %x\n", &a);

unsigned long ebp;

asm("mov %%rbp, %0" : "=r" (ebp));

printf("EBP: %lx\n", ebp);

int *p=&a;

printf(" %x\n", p);

unsigned long esp;

asm("mov %%rsp, %0" : "=r" (esp));

printf("ESP: %lx\n", esp);

return 0;

}

Output:

be2042f0

EBP: 7ff7be204300

b1e2042f0

ESP: 7ff7be2042d0

The value stored in the pointer p (i.e., the address of variable a) is the random number we saw earlier. You can test that *p (i.e., a) outputs 0, just like the 32-bit case.

Additionally, if you change the floating-point number to a floating-point pointer, the conversion works perfectly:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

double *a = 10;

printf("a = %d\n", a);

return 0;

}

Output:

a = 10

I couldn’t get a perfectly precise answer (i.e., exactly what happens at each step) because Apple does not publish documentation for its ABI or specific implementations. This is why many people dismiss this issue with “undefined behavior”—there’s no official documentation.

My guess is that the implementation includes pointer jumps inserted between different local variables. I noticed that a declared pointer and the address it points to are adjacent (I suspect the stack frame has empty spaces—e.g., 2 bytes of padding between variables and the stack top/bottom, which may be addresses), possibly for alignment purposes.

This may result in addresses of different lengths (I observed this during testing). I even suspect variables of different types may be stored in slightly different address regions.

This means when directly fetching content by an int address, you may end up with a “shorter address + subsequent content” or a “truncated longer address”—which will definitely cause errors.

In other words, the 64-bit issue is not about incorrect content formatting; instead, there are certain recognition and conversion mechanisms in place, and the problem lies with the addresses.

Using a pointer ensures you get the correct address of the double value. This is why testing showed that simply using a pointer resolved the issue.

Additionally, I noticed something: in some cases, the returned address is consistently 0x120a8—this may be something specific, but I couldn’t find any documentation about it.

During testing, I manually set the lower bits of

xmm0to 0, but the returned value was still0x120a8. This led me to guess that0x120a8is a recovery address—when an error occurs, execution jumps here and then returns to the next valid position.

This suggests that when printf processes two arguments, it may skip the first mismatched argument and process the second one first. Hence, the first output is the second argument (which matches the format specifier and prints correctly), and then it processes the first argument (causing the earlier issue).

This leads me to speculate that macOS’s printf checks each argument against its format specifier one by one—if there’s a mismatch, it moves to the next argument until a match is found. Why this guess? Modify the program as follows:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

double a = 10;

int b = 20;

printf("%d %f\n", a, b);

return 0;

}

We set the second format specifier to floating-point, but the corresponding argument is an integer. The output is reversed:

20 10.000000

It’s correct, but reversed—pretty weird, right?

This is why I believe there’s something “special” about macOS’s implementation. On Linux, these behaviors result in random numbers with no discernible pattern, which piqued my curiosity even more.

I hope these will help someone in need~

References/Further Reading

How does this program work? - Stack Overflow: Although this post is from 2010, it addresses the same problem as this article (including 64-bit behavior). The second-highest voted answer was very helpful to me—I referenced many of its examples (e.g., the reversed output test at the end). Unfortunately, Alok Singhal did not conduct in-depth research, and his reasoning was incorrect (he guessed it was due to different registers, like I did midway). However, the reversed output example helped form my final hypothesis—I wouldn’t have thought of the argument processing logic without it. Another post also guessed it was a register issue, which is why I mentioned xmm registers earlier, but it seems unrelated on macOS.

How does printf handle its arguments? - Stack Overflow: This post lists several printf implementations and methods. Although I didn’t use them in the article, they were still helpful.

Passing Parameters to printf - Halo Linux Services: This marketing article explains how printf retrieves arguments.

Stack and Frames Demystified CSCI: If you’re unfamiliar with operating systems, refer to this PPT for stack and frame concepts.