How to Do SIMD Programming in C++

I previously mentioned planning to abandon ISPC in favor of C++—ISPC evolves too quickly, and its documentation is poor, making it hard to keep up. Additionally, recent C++ standards have added solid support for official SIMD libraries, eliminating the need for third-party tools like ISPC. While ISPC still offers the best performance, I can no longer keep pace with its updates. However, you could pin to a specific ISPC version for development, as CPU instruction set updates are relatively slow.

Originally, I chose ISPC over C++ SIMD not for performance, but because C++ SIMD programming was quite “problematic”: implementations varied across compilers, and platform support was inconsistent.

Despite being developed by Intel, ISPC supports multiple platforms including ARM—Intel engineers even contributed the LLVM IR for ARM’s SIMD instructions.

This article marks the start of a series. Since parallel computing is not widely used, there’s much to learn.

What is SIMD Programming?

If you’re reading this, you likely have a background in computer science and have heard:

“GPUs are more parallel than CPUs.”

Strictly speaking, this is inaccurate. GPUs excel at the “D” (Multiple Data) part of SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data)—in other words, GPUs are powerful for parallel computing, not just general parallelism.

SIMD applies a single instruction to multiple data elements simultaneously. While there are many technical explanations, a simple analogy suffices: SIMD is like copying punishment in primary/secondary school—you can hold multiple pens to copy words at once. With one writing motion (time), you can write 2-5 words (5 pens means you’re truly skilled).

For example, to compute these 8 additions:

1 + 1

2 + 2

3 + 3

4 + 4

5 + 5

6 + 6

7 + 7

8 + 8

Serial computing requires 8 separate addition operations. However, all these operations follow the same pattern: load data → execute addition → store result. We can design circuits to perform this action on multiple registers simultaneously, drastically reducing execution time.

By design, GPUs are optimized for SIMD, while CPUs favor MIMD (Multiple Instruction Multiple Data). Thus, GPUs excel at parallel computing but struggle with multitasking. Modern CPUs also include SIMD support via instruction sets like SSE and AVX.

Here’s a real-world example: I previously implemented matrix multiplication with CUDA and ISPC. The floating-point performance of a 4C8T i5-10510U CPU was nearly identical to a 384-core MX250 GPU—with the same power consumption. This is a surprising result.

In recent years, Nvidia GPUs have grown exponentially in core count: the RTX 4090 delivers 145 TFLOPS of half-precision floating-point performance, leaving CPUs with no competitive advantage in this area.

But let’s focus on C++ SIMD. This detour helps explain why learning CPU SIMD programming is valuable. (I’m writing a separate blog on this topic, but it’s quite extensive—so it’s on hold for now.)

SIMD is also known as vectorization. If you’ve studied computer organization, you may have heard the term “vector processor”—the “vector” here refers to SIMD.

The Low-Level Approach: Intrinsics/Assembly

First, let’s define “Intrinsics”: compiler-provided functions that wrap assembly code for easier use (common on Windows and other compilers). For example, in my previous blog How to Measure Execution Time with rdtsc and C/C++ (Using Inline Assembly and Retrieving CPU TSC Frequency), I used inline assembly to get the CPU’s TSC frequency. However, Windows provides the intrin.h library, which includes __rdtsc() and __cpuid()—no manual assembly required.

When searching for C++ SIMD implementations online, you’ll either find third-party libraries or this intrinsic-based method.

SIMD intrinsics are spread across multiple libraries, and instructions for different instruction sets are scattered. To use them, look up the required functions in the Intel® Intrinsics Guide.

I won’t list which libraries correspond to each instruction set because there’s no consistent mapping across generations. You’ll need to look this up yourself. Creating an accurate table would be extremely time-consuming, and an incomplete one would be useless (though it might make this article seem more professional—I’d rather avoid that).

I won’t dive too deep into this method, as this article is just an introduction. While the barrier to entry is high (finding reliable learning resources), I’ll provide a simple example to demonstrate how to write SIMD code with intrinsics.

Example: Vector Addition with SIMD

Below is a parallel implementation of vector addition using AVX intrinsics:

#include <chrono>

#include <immintrin.h>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

const int VECTOR_SIZE = 4096; // Vector size

int main() {

// Initialize SIMD vectors (AVX: 8 floats per __m256)

__m256 vector1[VECTOR_SIZE / 8];

__m256 vector2[VECTOR_SIZE / 8];

__m256 result_simd[VECTOR_SIZE / 8];

// Initialize serial vectors for comparison

float vector_serial1[VECTOR_SIZE], vector_serial2[VECTOR_SIZE];

float result_serial[VECTOR_SIZE];

// Populate SIMD vectors (8 floats at a time)

for (int i = 0; i < VECTOR_SIZE; i += 8) {

vector1[i / 8] = _mm256_set_ps(1.0 * (i + 7 + 1),

1.0 * (i + 6 + 1),

1.0 * (i + 5 + 1),

1.0 * (i + 4 + 1),

1.0 * (i + 3 + 1),

1.0 * (i + 2 + 1),

1.0 * (i + 1 + 1),

1.0 * (i + 0 + 1));

vector2[i / 8] = _mm256_set_ps(2.5 * (i + 7 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 6 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 5 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 4 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 3 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 2 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 1 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 0 + 1));

result_simd[i / 8] = _mm256_set1_ps(0.0); // Set all 8 floats to 0.0

}

// Populate serial vectors

for (int i = 0; i < VECTOR_SIZE; i++) {

vector_serial1[i] = 1.0 * (i + 1);

vector_serial2[i] = 2.5 * (i + 1);

result_serial[i] = 0.0;

}

// ****************** SIMD Calculation ******************

auto start_simd = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

// Run 100,000 iterations to amplify time difference

for (int j = 0; j < 100000; ++j) {

for (int i = 0; i < VECTOR_SIZE / 8; i++) {

result_simd[i] = _mm256_add_ps(vector1[i], vector2[i]); // Add 8 floats at once

}

}

auto end_simd = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double> elapsed_simd = end_simd - start_simd;

// ****************** Serial Calculation ******************

auto start_serial = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

for (int j = 0; j < 100000; ++j) {

for (int i = 0; i < VECTOR_SIZE; i++) {

result_serial[i] = vector_serial1[i] + vector_serial2[i]; // Add 1 float at a time

}

}

auto end_serial = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double> elapsed_serial = end_serial - start_serial;

// Print execution times

std::cout << "SIMD Time taken: " << elapsed_simd.count() << " seconds" << std::endl;

std::cout << "Serial Time taken: " << elapsed_serial.count() << " seconds" << std::endl;

// Verify results (compare first 24 elements)

bool results_match = true;

float temp[24];

_mm256_storeu_ps(temp, result_simd[0]); // Extract 8 floats from result_simd[0]

_mm256_storeu_ps(&temp[8], result_simd[1]); // Extract 8 floats from result_simd[1]

_mm256_storeu_ps(&temp[16], result_simd[2]); // Extract 8 floats from result_simd[2]

for (int i = 0; i < 24; ++i) {

if (temp[i] != result_serial[i]) {

std::cout << "Mismatch at index " << i << ": SIMD result = " << temp[i]

<< ", Serial result = " << result_serial[i] << std::endl;

results_match = false;

break;

}

}

std::cout << "Results match: " << (results_match ? "Yes" : "No") << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Compilation & Execution

Compile with the -mavx flag (enables AVX instruction set support—omitting this will cause errors):

% clang++ simd.cpp -mavx && ./a.out

SIMD Time taken: 0.133898 seconds

Serial Time taken: 0.744482 seconds

Results match: Yes

The SIMD implementation is approximately 6x faster than the serial version. Unlike ISPC-generated code, this method won’t fully utilize the CPU (there’s room for further optimization), but it’s still vastly better than serial.

Why not use

-O3optimization? Compiler optimizations are often unpredictable. For low-level tests (e.g., memory I/O, instruction latency), it’s best to avoid optimizations. In this example, vectors are initialized with constant values. A smart compiler might optimize away the entire calculation (since the result is predictable). For instance, a loop that accumulates a fixed value might be replaced with a multiplication in-O3, which would invalidate the performance comparison. Here’s how the results vary with different optimization levels:

zhonguncle@ZhongUncle-Mac-mini simd % clang++ simd.cpp -mavx -O0 && ./a.out

SIMD Time taken: 1.42122 seconds

Serial Time taken: 7.51199 seconds

Results match: Yes

zhonguncle@ZhongUncle-Mac-mini simd % clang++ simd.cpp -mavx -O1 && ./a.out

SIMD Time taken: 0.858161 seconds

Serial Time taken: 3.23735 seconds

Results match: Yes

zhonguncle@ZhongUncle-Mac-mini simd % clang++ simd.cpp -mavx -O2 && ./a.out

SIMD Time taken: 0.875178 seconds

Serial Time taken: 0.850877 seconds

Results match: Yes

zhonguncle@ZhongUncle-Mac-mini simd % clang++ simd.cpp -mavx -O3 && ./a.out

SIMD Time taken: 0.840105 seconds

Serial Time taken: 0.805046 seconds

Results match: Yes

Code Explanation

This method is essentially assembly in disguise—you must manually load, manipulate, and store data (no “one-size-fits-all” abstraction). Below is a breakdown, with tips on reading the official documentation:

1. Data Conversion: float → __m256

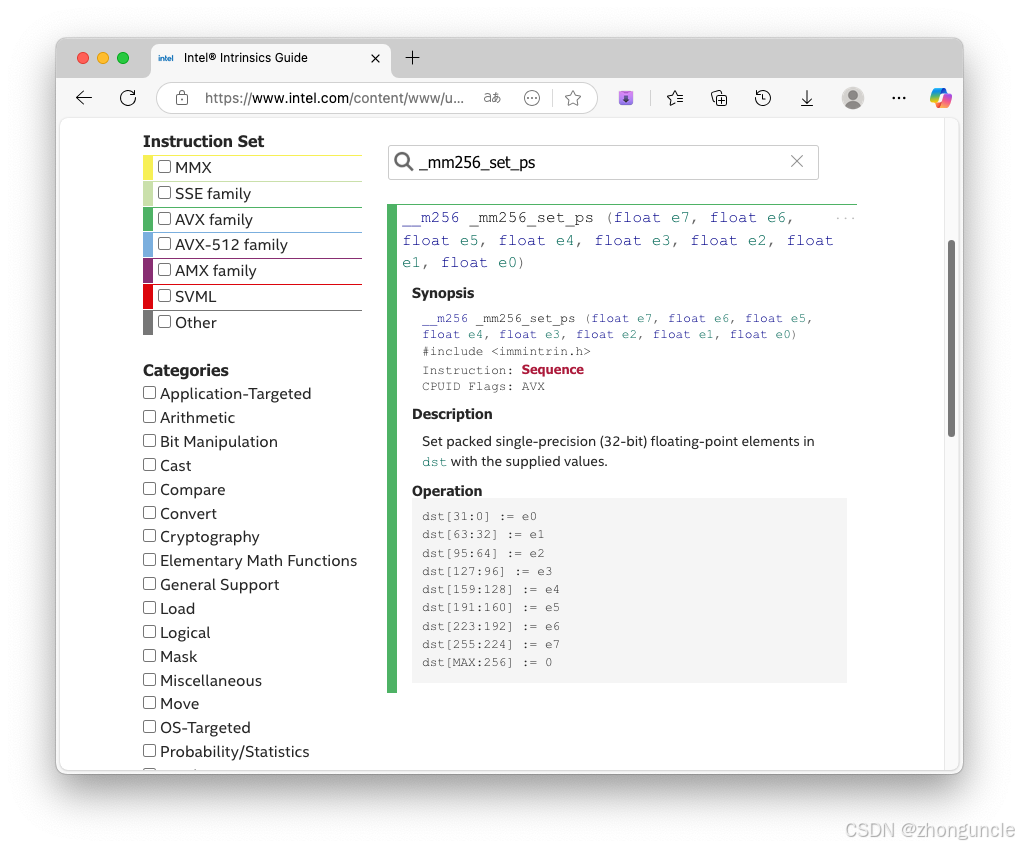

AVX instructions require data in the __m256 format (8 floats per register). The _mm256_set_ps function initializes a __m256 value:

As shown in the documentation, _mm256_set_ps accepts 1-8 single-precision floats. Examples from the code:

// Initialize 8 floats (note: reverse order in the function call)

vector2[i / 8] = _mm256_set_ps(2.5 * (i + 7 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 6 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 5 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 4 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 3 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 2 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 1 + 1),

2.5 * (i + 0 + 1));

// Initialize all 8 floats to 0.0

result_simd[i / 8] = _mm256_set1_ps(0.0);

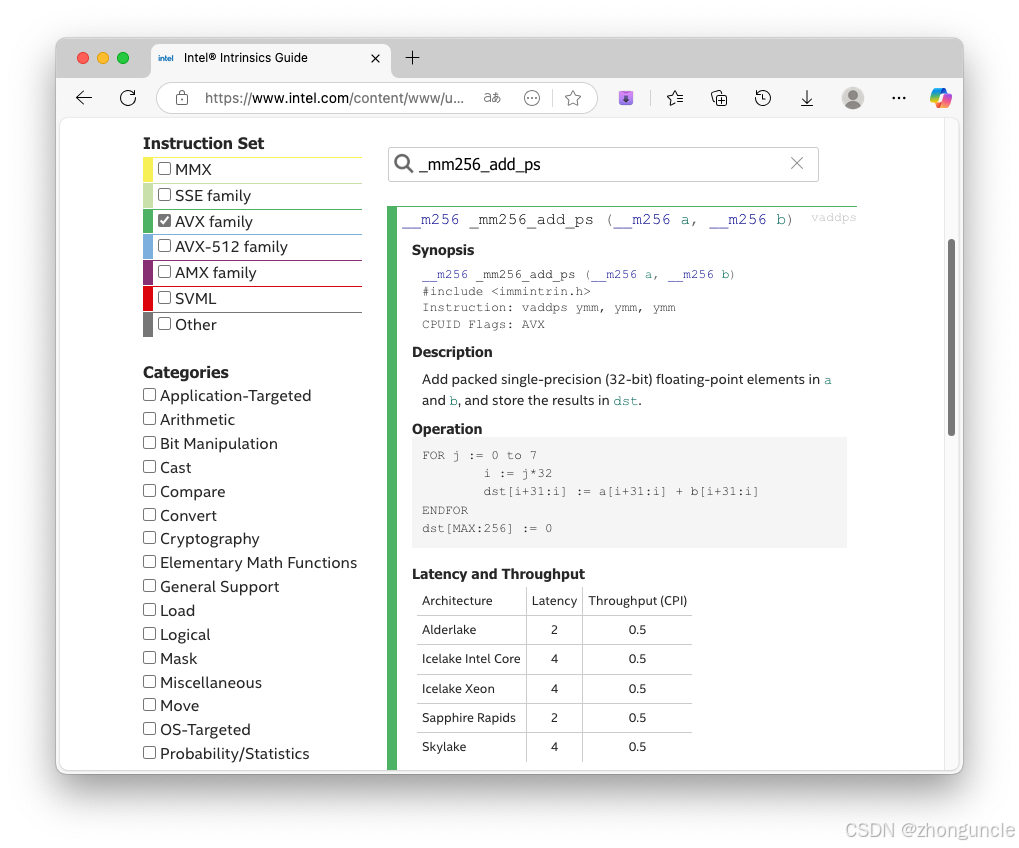

2. SIMD Calculation

_mm256_add_ps performs parallel addition on 8 floats (one __m256 register):

This is why the loop increments by 8 (VECTOR_SIZE / 8):

for (int i = 0; i < VECTOR_SIZE / 8; i++) {

result_simd[i] = _mm256_add_ps(vector1[i], vector2[i]);

}

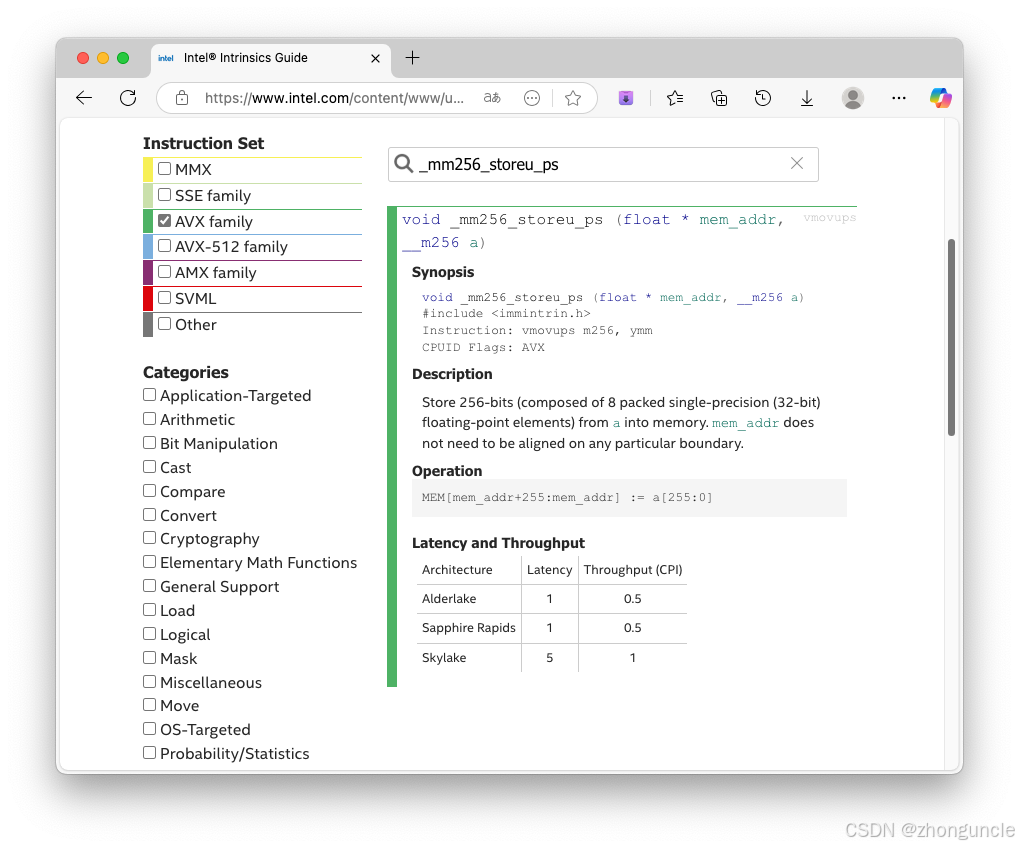

3. Data Conversion: __m256 → float

After calculation, use _mm256_storeu_ps to extract 8 floats from a __m256 register into a regular float array:

Example (extract 24 floats total):

_mm256_storeu_ps(temp, result_simd[0]); // Extract first 8 floats

_mm256_storeu_ps(&temp[8], result_simd[1]); // Extract next 8 floats

_mm256_storeu_ps(&temp[16], result_simd[2]); // Extract next 8 floats

Drawbacks of Intrinsics

- Verbose code: Manual data management (loading/storing) adds boilerplate.

- Requires manual optimization: You must handle instruction scheduling, memory alignment, and vectorization yourself.

The Simplest Approach: GCC’s Experimental <experimental/simd>

Another option is GCC’s experimental <experimental/simd> library.

The C++26 standard will introduce a standard SIMD library, but none of the four major compilers (GCC, Clang, MSVC, Apple Clang) have implemented it yet. In a few years, there may be a universal solution—but for now, no cross-compiler SIMD library exists.

Fortunately, most <cmath> functions have been reimplemented for SIMD, making this library suitable for most use cases.

Example: SIMD with <experimental/simd>

This method is far simpler. Below is an annotated example from cppreference.com:

#include <experimental/simd>

#include <iostream>

#include <string_view>

namespace stdx = std::experimental;

// Helper function to print SIMD vectors

void println(std::string_view name, auto const& a)

{

std::cout << name << ": ";

for (std::size_t i{}; i != std::size(a); ++i)

std::cout << a[i] << ' ';

std::cout << '\n';

}

// SIMD-enabled absolute value function

template<class A>

stdx::simd<int, A> my_abs(stdx::simd<int, A> x)

{

where(x < 0, x) = -x; // Apply operation to elements where condition is true

return x;

}

int main()

{

// stdx::native_simd<int>: SIMD array with compiler-determined size (matches hardware)

const stdx::native_simd<int> a = 1; // Set all elements to 1

println("a", a);

// Initialize elements with a lambda (value = index - 2)

const stdx::native_simd<int> b([](int i) { return i - 2; });

println("b", b);

// SIMD vector addition (parallelized automatically)

const auto c = a + b;

println("c", c);

// Apply SIMD absolute value

const auto d = my_abs(c);

println("d", d);

// Element-wise multiplication (d[i] * d[i])

const auto e = d * d;

println("e", e);

// Reduce: sum all elements of e (inner product of d with itself)

const auto inner_product = stdx::reduce(e);

std::cout << "inner product: " << inner_product << '\n';

// stdx::fixed_size_simd: SIMD array with user-specified size (16 elements of long double)

const stdx::fixed_size_simd<long double, 16> x([](int i) { return i; });

println("x", x);

// SIMD-enabled math functions (cos, sin, pow)

println("cos²(x) + sin²(x)", stdx::pow(stdx::cos(x), 2) + stdx::pow(stdx::sin(x), 2));

}

Compilation & Execution

$ g++ -std=c++20 simd.cpp && ./a.out

a: 1 1 1 1

b: -2 -1 0 1

c: -1 0 1 2

d: 1 0 1 2

e: 1 0 1 4

inner product: 6

x: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

cos²(x) + sin²(x): 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

Controlling native_simd Size

The size of native_simd is determined by the target platform during compilation. To specify the instruction set (e.g., AVX2), add the -mavx2 flag:

$ g++ -std=c++20 simd.cpp -mavx2 && ./a.out

a: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

b: -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5

c: -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

d: 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

e: 1 0 1 4 9 16 25 36

inner product: 92

x: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

cos²(x) + sin²(x): 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

With AVX2, native_simd<int> uses 8 elements (matches AVX2’s 256-bit registers). For AVX (128-bit registers), use -mavx:

$ g++ -std=c++20 simd.cpp -mavx && ./a.out

a: 1 1 1 1

b: -2 -1 0 1

c: -1 0 1 2

d: 1 0 1 2

e: 1 0 1 4

inner product: 6

x: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

cos²(x) + sin²(x): 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

Other SIMD methods exist (e.g., Intel Compiler-specific extensions), but they are not compiler-agnostic. I rarely use the Intel Compiler, so I won’t cover them here—but I’ve included relevant resources in the references below.

I hope these will help someone in need~

References

- Intel® Intrinsics Guide: Search for SIMD intrinsics and their documentation.

- SIMD library - cppreference.com: Official documentation for

<experimental/simd>. - std::simd - Dr. Matthias Kretz: 2023 PPT introducing C++’s upcoming standard SIMD library.

- Intel C++ Intrinsic Reference: Comprehensive guide to Intel’s C++ intrinsics.

- Efficient Vectorisation with C++ - chryswoods.com: Practical guide to vectorization in C++ (includes compiler setup and SIMD examples).

The first section covers parallel

forloops (unrelated to SIMD but useful for parallel computing). - Advanced Parallel Programming in C++ - Patrick Diehl et al.: High-level overview of parallel computing in C++ (covers async programming, parallel algorithms, and HPX).

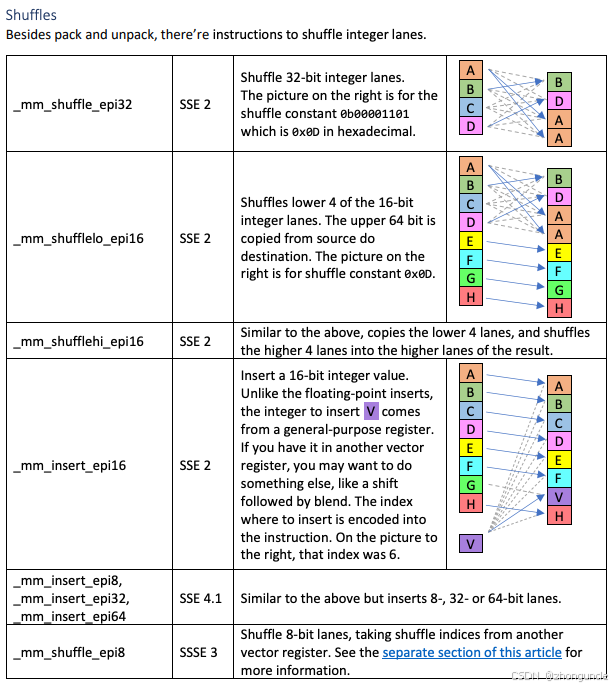

- SIMD for C++ Developers - const.me: Personal guide with excellent visual explanations of SIMD concepts:

- An Introduction to Parallel Computing in C++ - CMU: Carnegie Mellon University’s guide to parallel computing (introduces a third-party library and core concepts).

- C++ Classes and SIMD Operations - Intel® oneAPI DPC++/C++ Compiler Guide: SIMD documentation for the Intel Compiler (relevant if you use it).