What Is Hamming Code? A Deep Dive into Error Detection and Correction

I first learned about Hamming codes a few years ago when I watched 3Blue1Brown’s video But what are Hamming codes? The origin of error correction - 3Blue1Brown’s YouTube. I then looked into Hamming himself and thought he was brilliant. Later, I was impressed to discover in The UNIX Hater’s Handbook that Hamming was actually Brian Kernighan’s (co-author of the C language bible The C Programming Language, commonly known as K&R) mentor at Bell Labs and the third Turing Award winner. It felt like a sense of historical inheritance, so I read his Turing Award lecture. Honestly, many of Hamming’s viewpoints are fascinating, and from Brian’s descriptions, he was also a humorous person—feel free to check it out if you’re interested.

I never remember things from math popularization videos; maybe our “wavelengths” don’t match. So I decided to research Hamming codes myself.

What Is Hamming Code?

In his original paper, Hamming described an error-detecting and error-correcting code: a Systematic Code.

The structure of a systematic code is as follows: Assume there are n binary bits, where m bits are used to represent data, and k bits are used for error detection and correction. This gives a redundancy rate R = n/m, which is the minimum number of bits required to transmit the same information.

At the time, channel capacity was truly limited, so Hamming emphasized multiple times at the beginning of the paper that error detection and correction would reduce channel utilization.

The paper constructs three types of minimum redundancy codes:

- Single error detection code (parity check code);

- Single error correction code;

- Single error correction and double error detection code.

The latter two are both called Hamming Codes—named after Hamming, they are sometimes referred to as the Hamming code family. However, the single error correction code is the most critical in terms of core ideas.

Single Error Detection Code (Parity Check Code)

This code uses the highest bit to detect errors. If the total number of 1s in all bits is even, the highest bit is set to 1; otherwise, it is set to 0.

Following the earlier assumption: with n binary bits (m data bits + k parity bits), the redundancy rate is:

There’s not much to say about this—it’s simple and has been used in machines nearly a century ago. As the amount of transmitted data increases, the likelihood of errors grows, demanding new technologies.

Take the smallest example: We want to send 1. The parity bit is also 1, so we transmit 11:

Transmit: 11

Receive: 10

The parity bit does not match the actual number of 1s, so an error is detected—but it cannot be corrected.

Single Error Correction Code

To correct an error, we need to know its position. How to achieve this?

Remember we’re working with binary—we need to identify the position (i.e., which bit) is incorrect.

Hamming introduced a concept called Checking Number, which essentially involves multiple parity checks in a specific order. This is the most ingenious part of Hamming codes.

With the parity check code, we can only know that one bit is wrong—but how do we find which one?

Let’s use the 4-bit binary number 12 (i.e., 1100) as an example. To locate an error among the 4 data bits, m and k must satisfy the following formula (explained later), where m = data bits and k = parity/correction bits:

Thus, 3 additional parity bits are needed to find the error position.

This means we need to transmit 7 bits—this is crucial; be sure to track the bit count change. From now on, when considering single-bit errors, we must include these parity bits.

In the case of at most one error, there are 8 possibilities: no error, or an error in bit 1~7.

Hamming’s approach is brilliantly simple: If you can’t locate the error directly, narrow it down bit by bit. First, look at the rightmost bit of the binary representation of the positions:

|

1=0001

3=0011

5=0101

7=0111

(Range: 0~7, covering all possible error scenarios above)

This gives us bits 1, 3, 5, 7. Then take two more groups (since we have 3 parity bits total):

|

2=0010

3=0011

6=0110

7=0111

|

4=0100

5=0101

6=0110

7=0111

Combine these three groups:

Group 1: 1 3 5 7

Group 2: 2 3 6 7

Group 3: 4 5 6 7

You’ll notice these three groups cover the entire range 1~7.

Additionally, using only 2 groups would leave one position uncovered, while 4 groups would be redundant (3 groups are sufficient for full coverage). Hence, we derive the earlier formula:

\[2^k \ge m+k+1\]The 1 in the formula accounts for the “no error” scenario.

Hamming then performs parity checks on these three groups. The results of the parity checks are stored in the first position of each group (where x = parity bit, unknown initially):

Sequence: x x 1 x 1 0 0

Group 1: 1 3 5 7 --- Even parity → 0

Sequence: 0 x 1 x 1 0 0

Group 2: 2 3 6 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Sequence: 0 1 1 x 1 0 0

Group 3: 4 5 6 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Final sequence: 0 1 1 1 1 0 0

This result matches exactly what’s in the original paper:

How to use this result?

Assume an error occurs in the 5th bit:

|

0 1 1 1 0 0 0

The receiver performs three parity checks (same method as encoding) using the bit positions:

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

Group 1: 1 3 5 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Checking Number: 1

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

Group 2: 2 3 6 7 --- Even parity → 0

Checking Number: 0 1 (inserted at the front)

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

Group 3: 4 5 6 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Checking Number: 1 0 1

The binary value 101 converts to decimal 5—the error is in the 5th bit. This 101 is the Checking Number mentioned earlier, which indicates the error position.

Another example: What if there’s no error?

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 1 0 0

Group 1: 1 3 5 7 --- Even parity → 0

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 1 0 0

Group 2: 2 3 6 7 --- Even parity → 0

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 1 0 0

Group 3: 4 5 6 7 --- Even parity → 0

Checking Number: 000

A result of 000 means no error (0 is not in the range 1~7).

Isn’t this amazing? How does converting between these groups instantly reveal the error position?

Let’s return to the three groups:

Group 1: 1 3 5 7

Group 2: 2 3 6 7

Group 3: 4 5 6 7

These groups depend only on bit positions, not the data being transmitted. Let’s analyze the groups themselves.

Suppose an error occurs in one of the four positions in Group 1. From the other two groups, we know bits 3, 5, 7 are correct—so the error must be in bit 1. This matches the binary sequence 001 we obtained.

Each group combination uniquely identifies a bit position—hence the need for full coverage (no gaps, no redundancy).

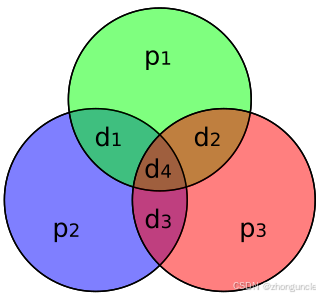

Additionally, if you plot these groups, it matches the Hamming code diagram on Wikipedia: the final intersection is unique (the erroneous bit):

Single Error Correction and Double Error Detection Code

This code builds on the single error correction code by adding an extra parity bit at the end to check the entire sequence.

Important note: Single error correction and double error detection does not mean correcting one error while detecting two. Instead, it either corrects one error or detects two errors.

Three scenarios:

- No error: All parity checks (including the final extra bit) pass (even parity) → no error.

- One error: The final extra parity check fails → the checking number indicates the error position.

- Two errors: The final extra parity check passes, but the checking number is non-zero (indicating errors) → two errors detected.

Continuing with the earlier sequence 0 1 1 1 1 0 0, adding an extra parity bit gives:

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 x --- Even parity → 0

Final sequence: 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0

Again, assume an error in the 5th bit:

|

0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0

Final bit: | --- Odd parity → 1 (possible single error)

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0

Group 1: 1 3 5 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Checking Number: 1

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0

Group 2: 2 3 6 7 --- Even parity → 0

Checking Number: 0 1 (inserted at the front)

Sequence: 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0

Group 3: 4 5 6 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Checking Number: 1 0 1 --- Non-zero → single error (correctable)

The 5th bit is corrected as before.

Now assume errors in the 2nd and 5th bits:

| |

0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

Then:

Sequence: 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

Final bit: | --- Even parity → 0 (possible no error or two errors)

Sequence: 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

Group 1: 1 3 5 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Checking Number: 1

Sequence: 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

Group 2: 2 3 6 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Checking Number: 1 1 (inserted at the front)

Sequence: 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

Group 3: 4 5 6 7 --- Odd parity → 1

Checking Number: 1 1 1

The checking number still points to a single position, but two errors are actually present.

Hamming Distance

Hamming referred to binary numbers that differ by 1 bit as having a distance of 1. Similarly, a difference of 2 bits means a distance of 2, and so on. The term “Hamming Distance” is used today but was not in the original paper.

Hamming treated a set of binary numbers as vectors in an n-dimensional space. By observing that 1 error changes one coordinate and 2 errors change two coordinates, he derived a matrix called the distance ($D(x,y)$), or Hamming distance.

Additionally, Hamming distance is defined as the minimum number of substitutions required to convert one string into another (represented as equivalence classes in the original paper).

Errors cannot be detected if the entire code is corrupted:

- To detect

derrors, the Hamming distance must bed+1; - To correct

derrors, the Hamming distance must be2d+1.

I hope these will help someone in need~

References

- Error detecting and error correcting codes: Hamming’s original 1950 paper on Hamming codes.