High-Precision Time Measurement in C/C++ on Windows: A Guide to QPC (QueryPerformanceCounter)

Updated on April 11, 2024 Thanks to commenters for pointing out that when I wrote Measuring Function/Feature Execution Time in C/C++: Serial vs. Parallel, and Practical Comparison of Three Methods, I only tested it on Unix-like systems such as Linux and macOS, and overlooked Windows compatibility.

This article only covers native (Microsoft-provided) time measurement functions on Windows. Third-party high-precision time measurement libraries are not discussed here.

The optimal method for high-precision time interval measurement on Windows is QPC (QueryPerformanceCounter).

QPC is a Difference Clock that does not rely on external time references—unlike the absolute time (e.g., “2020/3/18 14:29:59”, also vividly called “wall-clock time”) we commonly use (similar to clock()). Additionally, QPC is unaffected by standard/system time adjustments, analogous to CLOCK_MONOTONIC in clock_gettime().

QPC uses hardware counters to calculate time. On most x86-based devices, QPC measures time by accessing the processor’s TSC (Time Stamp Counter). However, the BIOS on some devices may misconfigure CPU features (e.g., setting TSC to variable mode), introducing external interference. For multi-processor systems, dual TSC sources may be unsynchronized. In such cases, Windows uses platform counters or other motherboard timers instead of TSC—adding an overhead of 0.8 to 1.0 microseconds. While QPC primarily uses TSC, Microsoft officially discourages directly retrieving TSC values via RDTSC/RDTSCP (the latter specifies a CPU core). This drastically reduces software compatibility (e.g., programs may fail or return large errors on systems with variable TSC or no TSC support). Most C/C++ compilers provide built-in functions like

__builtin_ia32_rdtsc()or__builtin_ia32_rdtscp(), allowing you to get the counter value withuint64_t rdtsc = rdtsc();and calculate the difference (similar toclock()). However, you must compute the TSC frequency to get accurate time. TSC is just one mechanism—Windows 8 and later use multiple hardware counters to detect errors and apply compensation as much as possible.

QPC’s precision is two orders of magnitude lower than clock_gettime() (100 nanoseconds vs. 1 nanosecond), but this is sufficient for most practical scenarios.

QPC Usage Example

Below is a practical example (the first line indicates the required header file):

#include <windows.h>

int main()

{

LARGE_INTEGER StartingTime, EndingTime, ElapsedMicroseconds;

LARGE_INTEGER Frequency;

QueryPerformanceFrequency(&Frequency); // Get counter frequency

QueryPerformanceCounter(&StartingTime); // Record start time

// ... Code to be measured goes here

QueryPerformanceCounter(&EndingTime); // Record end time

// Calculate and print time in microseconds (μs)

printf(" %.1f us", 1000000*((double)EndingTime.QuadPart - StartingTime.QuadPart)/ Frequency.QuadPart);

}

Understanding LARGE_INTEGER

LARGE_INTEGER is a Windows union for storing 64-bit integers, defined as:

typedef union _LARGE_INTEGER {

struct {

DWORD LowPart; // Lower 32 bits

LONG HighPart; // Higher 32 bits

} DUMMYSTRUCTNAME;

struct {

DWORD LowPart;

LONG HighPart;

} u;

LONGLONG QuadPart; // 64-bit integer (preferred if supported)

} LARGE_INTEGER;

Use QuadPart if your compiler natively supports 64-bit integers; otherwise, use LowPart + HighPart. The example above uses QuadPart to read the 64-bit counter value.

If you’re unfamiliar with unions, refer to my blog: What is Union? Where do I need to use it?

Key Functions Explained

QueryPerformanceFrequency: Retrieves the hardware counter’s oscillator frequency (required for converting counts to time).QueryPerformanceCounter: Captures the current counter value at the start/end of the measured code.- Time calculation formula:

(EndingCount - StartingCount) / Frequency

The1000000multiplier converts the result to microseconds—use1000for milliseconds or1000000000for nanoseconds.

Precision Notes

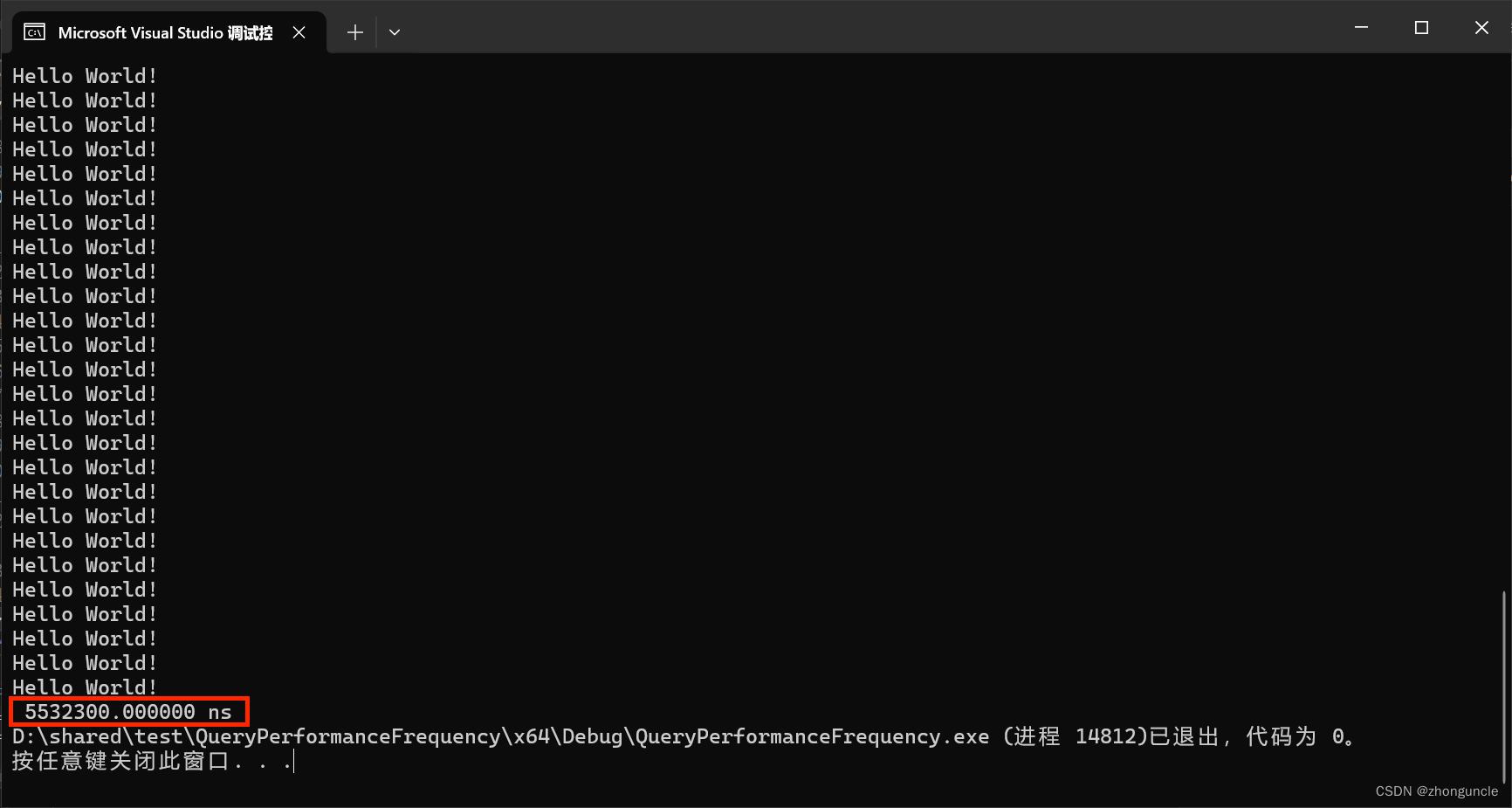

QPC’s 100-nanosecond precision means the last two digits of nanosecond values are always 0 (see screenshot below):

Use appropriate format specifiers:

%.1ffor microseconds (1 decimal place)%.f/%.0ffor nanoseconds (no decimal places)

Additional decimal places exceed QPC’s precision (though you may use them for alignment if needed).

I hope these will help someone in need~

References/Further Reading

- Acquiring high-resolution time stamps - Microsoft Learn: Official guide to high-precision time retrieval on Windows. The Resolution, Precision, Accuracy, and Stability section explains error sources in hardware counter-based time measurement (highly recommended).

- Time - Microsoft Learn: Comprehensive overview of time-related functions on Windows.

- LARGE_INTEGER union (winnt.h) - Microsoft Learn: Official documentation for

LARGE_INTEGER.