Measuring Function/Feature Execution Time in C/C++: Serial vs. Parallel, and Practical Comparison of Three Methods

This article serves as a complete summary of measuring the execution time of functions or features in C/C++. At the end, we’ll demonstrate a comparison of three methods.

Updated on March 14, 2025

Recently, while working with C++, I noticed thechronolibrary has become increasingly prevalent since C++20. I learned its usage and wrote a supplementary blog post: Measure Function Execution Time with C++20 chrono: Simplified Timing (System Clock & Steady Clock)

The Most Common Method: clock()

The most widely used approach is to record two CPU time points with clock_t using clock(), then calculate the difference. Its main advantage is simplicity and ease of use, as shown below (the first line indicates the required header file):

#include <time.h>

.....

clock_t begin = clock();

// ... Code to be measured goes here

clock_t end = clock();

int duration = (end - begin) / CLOCKS_PER_SEC;

Important Notes:

- On macOS,

CLOCKS_PER_SECis 1,000,000—meaning the unit of(end - begin)is microseconds. Thus, dividing byCLOCKS_PER_SECconverts it to seconds. - The type of

clock_tvaries across platforms: some use integers, others floating-point numbers. For floating-pointclock_t,CLOCKS_PER_SECmay be omitted—always refer to your system’stime.hfor details. - The term “clock” here refers to CPU clock cycles, not wall-clock time. This method originated in an era when computers had fixed clock speeds (still true for some calculators or microcontrollers today).

Key Limitation:

This method measures CPU time used by the process, not actual wall-clock time. This makes it inaccurate for non-CPU-bound programs. Most critically, it fails completely for parallel computing programs—you cannot simply divide by the number of cores to get the correct time.

Why? Because it sums the CPU time used across multiple cores. For serial programs (which use ~99% of a single core), this works perfectly. However, for parallel programs running on a 6-core CPU, even 570% CPU utilization (excellent for real-world scenarios) would report a duration of 27 seconds for a task that actually took only 5 seconds.

I discovered this issue while writing parallel computing programs with ISPC, which led me to explore alternative methods—starting with the next one.

timespec

timespec provides simple calendar time or elapsed time measurement. Using calendar time solves the parallel program timing issue from the previous section. However, its “simplicity” comes with a tradeoff: integer-based time representation, meaning the minimum precision is 1 second (unlike the microsecond precision of clock()). For testing complex functions or programs, this is acceptable—after all, the performance difference between 30 minutes and 31 minutes is only ~3.22%.

Usage (first line indicates required header file):

#include <time.h>

time_t begin = time(NULL);

// ... Code to be measured goes here

time_t end = time(NULL);

int duration = (end - begin);

As you can see, it’s even simpler than clock().

Limitation:

For small-scale tests, the integer precision causes excessive error. For example, 0.6 seconds is three times faster than 1.8 seconds, but the integer result would show only a 2x difference—or even 1x (you’ll see why in the demonstration later). Thus, we need a method that supports both parallel computing and higher precision.

clock_gettime()

clock_gettime() perfectly meets these requirements, but it’s slightly more complex to use.

Updated on April 15, 2024

Thanks to a commenter for pointing out that I only testedclock_gettime()on Unix-like systems (Linux/macOS) and overlooked Windows compatibility. After researching, I wrote a dedicated guide for Windows: High-Precision Time Measurement in C/C++ on Windows: A Guide to QPC (QueryPerformanceCounter)

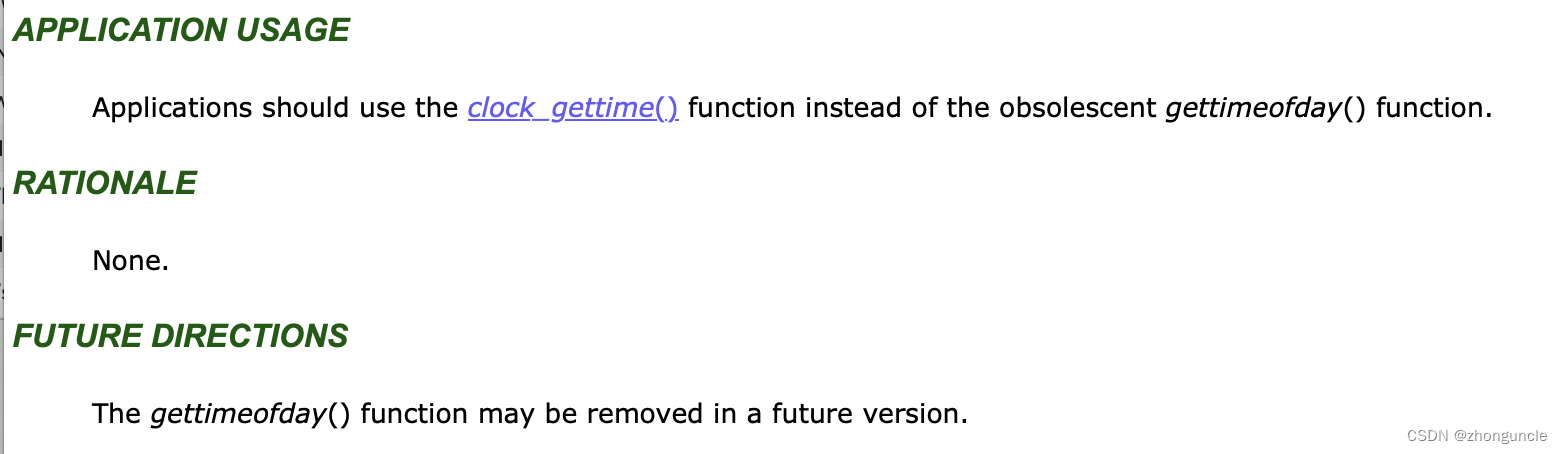

I discovered clock_gettime() while browsing documentation. Initially, I found gettimeofday(), but after checking the IEEE standard documentation https://pubs.opengroup.org/onlinepubs/9699919799/functions/gettimeofday.html, I learned:

- The “FUTURE DIRECTIONS” section states

gettimeofday()may be deprecated in the future. - The “APPLICATION USAGE” section recommends using

clock_gettime()instead ofgettimeofday().

Naturally, I switched to clock_gettime().

Complexity: High Precision

The complexity of clock_gettime() stems from its ultra-high precision. Here’s how to use it (first line indicates required header file):

#include <time.h>

struct timespec start;

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &start);

// ... Code to be measured goes here

struct timespec end;

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &end);

double duration = (double)(end.tv_nsec - start.tv_nsec) / 1e9 + (double)(end.tv_sec - start.tv_sec);

Two Key Clock Modes:

CLOCK_MONOTONIC:- Counts time continuously from system boot (no jumps, unless manually adjusted).

- Use this for serious timing tasks—its monotonic nature avoids negative durations.

CLOCK_REALTIME:- Represents system-level real-time clock (slightly lower precision than

CLOCK_MONOTONIC, but faster). - Suitable for simple, non-critical timing scenarios.

- Represents system-level real-time clock (slightly lower precision than

What Does “Continuous and Non-Jumping” Mean?

If your computer is offline for a long time, the motherboard battery dies, or there’s no external timer, the system time may be incorrect on boot (requiring network synchronization). This is an extreme case, but it illustrates how computers rely on internal/external clocks—these clocks stop or reset when powered off and have limited precision.

In practice, system time may occasionally adjust slightly to maintain accuracy (unnoticeable to humans, e.g., a few nanoseconds). However, this adjustment can cause negative durations if it occurs during timing—hence the need for CLOCK_MONOTONIC.

Time Calculation Explanation:

The time difference formula is longer because clock_gettime() returns time in two parts:

tv_sec: Seconds (integer type).tv_nsec: Nanoseconds (long integer type).

Note: A forum user mentioned that tv_nsec used to be microseconds on older macOS versions, but it’s now nanoseconds on modern systems.

To compute the total duration, we convert nanoseconds to seconds and add it to the second difference.

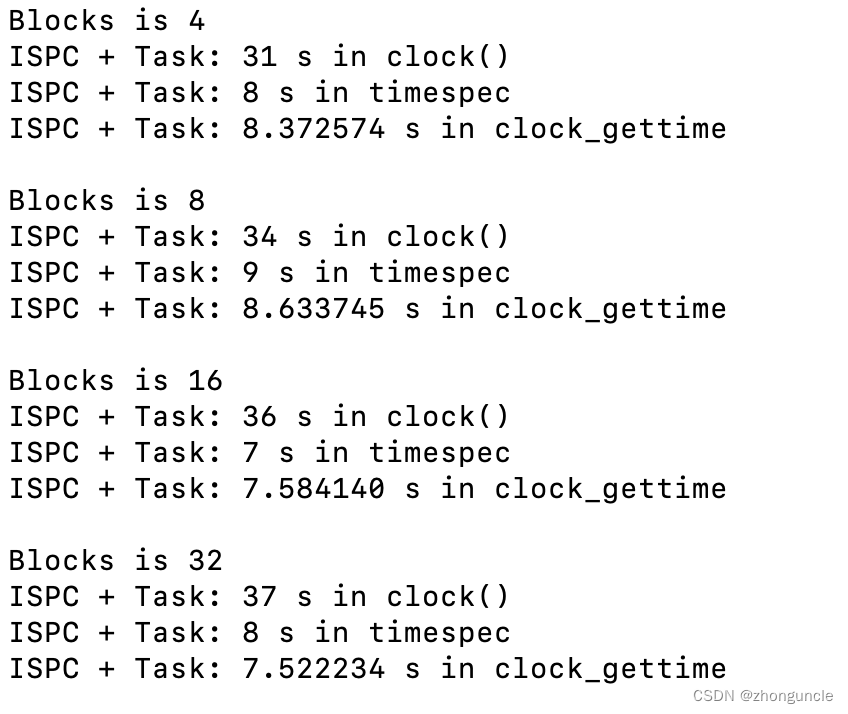

Practical Demonstration: Comparison of Three Methods

Below is a comparison of the three methods on a parallel computing program. You can infer the test device uses a 6-core 6-thread CPU:

As you can see, the differences can be significant.

References

- 21.2 Time Types - GNU

- 21.4 Processor And CPU Time - GNU

- clock_gettime(3) — Linux manual page

- What is the proper way to use clock_gettime()? - Stack Overflow

- clock_getres, clock_gettime, clock_settime - clock and timer functions - IEEE

I hope these will help someone in need~