Measure Function Execution Time with C++20 chrono: Simplified Timing (System Clock & Steady Clock)

I previously wrote a blog post: Measuring Function/Feature Execution Time in C/C++: Serial vs. Parallel, and Practical Comparison of Three Methods. Recently, I discovered new capabilities of the chrono library.

While

chronowas added in C++11, it saw little adoption back then—its design was incomplete, and it offered no advantages over other timing methods. Fortunately, C++20 introduced significant revisions that made it far more useful, leading to its growing prevalence in modern C++ code.

This article uses features exclusive to C++20—earlier versions may work but are not guaranteed.

This method is less universal than the ones in my previous post, but it drastically reduces code volume (way less code).

However, I can’t definitively say which approach is better or worse. Unlike the methods in my earlier blog (which I used extensively and understand their pros/cons thoroughly), this is just a record of chrono usage that I may update later. I’m writing this because chrono is appearing more frequently in modern C++ code—at the very least, you should understand how it works.

The word “chrono” is an abbreviation of “chronometer” (an astronomical clock). Another theory states it derives from the Greek word “chrónos”—in Greek mythology, Chrónos is the personification of time (Father Time).

According to documentation, chrono can be seen as a successor to the older time library. Its primary feature is formatted time printing (unsurprising, as most modern languages have standardized time libraries, while C++’s traditional time utilities are outdated and overly complex). This makes its timing logic different from methods like clock_gettime:

chronomeasures time by capturing system clock values and calculating the difference.clock_gettimerelies on hardware timers/counters on the device.

Of course, you can also use counters with chrono—more on that later.

This article focuses on measuring elapsed time (execution duration). Formatted system time printing is not covered here.

Measure Execution Time with System Clock

Verbose Version

First, here’s the full, non-simplified code (included to explain the underlying mechanics; a simplified version follows):

#include <chrono>

#include <iostream> // Added for std::cout/endl (omitted in original but required for compilation)

int main() {

std::chrono::time_point<std::chrono::system_clock> start = std::chrono::system_clock::now();

// ... Code to be measured goes here

std::chrono::time_point<std::chrono::system_clock> end = std::chrono::system_clock::now();

std::chrono::duration<double, std::nano> elapsed = end - start;

// Note: Use elapsed.count() (not just elapsed) to get the numerical value

std::cout << elapsed.count() << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Explanation of the Verbose Code

system_clock::now()captures the current system time for start/end points. To use hardware counters instead, replacesystem_clockwithsteady_clock(example below).- The

std::chrono::duration<double, std::nano>type defines the elapsed time:double: Uses double-precision floating-point for the value.std::nano: Sets the time unit to nanoseconds (astd::ratioconstant).

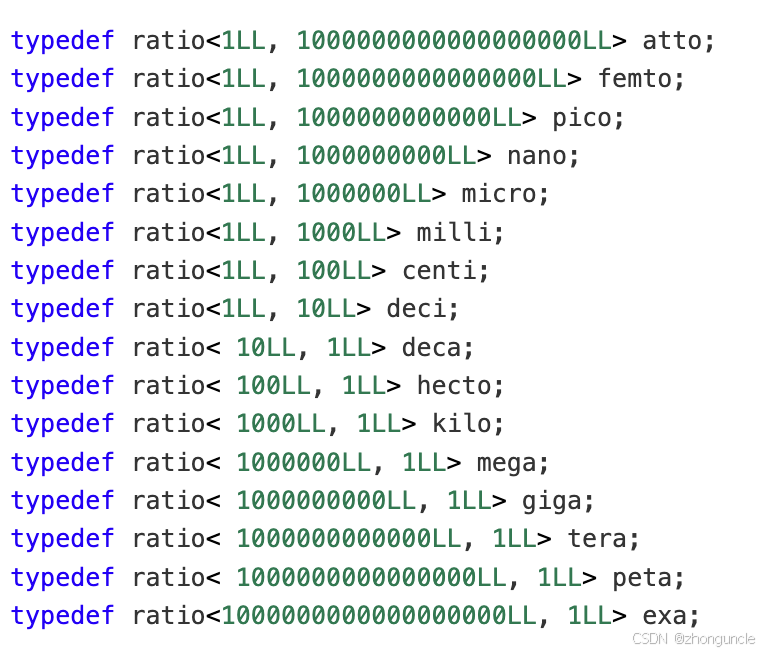

This is where chrono differs from traditional methods: instead of manual unit conversions (which I always copy-paste—who writes them from scratch every time?), std::nano (and similar constants) handle units automatically. These constants represent ratios and can be replaced with other units (note: not all are time-related):

Important: These are ratios. For example, using std::deci (meaning 1/10) would return a value 10x the actual seconds—remember to divide by 10 when printing.

This is just an example—practically, you can use

std::nanoand divide by1e9to get seconds (equivalent to usingstd::second).

Simplified Version (C++20)

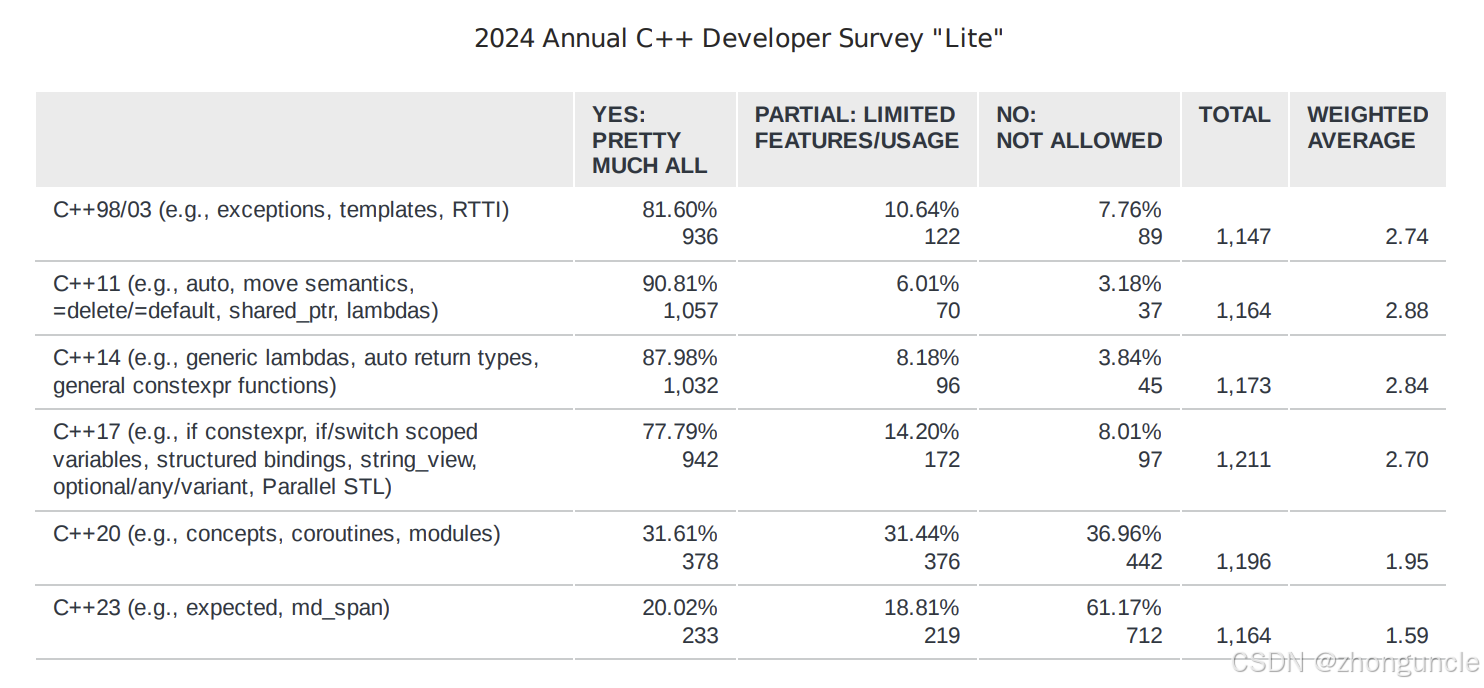

C++20 simplifies this significantly. According to a C++ Foundation survey, only 30% of developers used C++20 in 2024—but modern C++ is evolving fast:

You can simplify the code by using auto (stop obsessing over explicit types in C++20!):

#include <chrono>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Using std::literals lets you use `1s` for 1 second, `1ms` for 1 millisecond, etc.—extremely convenient

using namespace std::literals;

auto start = std::chrono::system_clock::now();

// ... Code to be measured goes here

auto end = std::chrono::system_clock::now();

std::cout << "ms: " << (end - start) / 1ms << std::endl;

std::cout << "s: " << (end - start) / 1s << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Sample output:

$ ./a.out

ms: 2317

s: 2

This code is drastically shorter and eliminates manual unit conversion entirely!

Measure Execution Time with Hardware Counters (Steady Clock)

Returning to steady_clock (hardware counter-based timing): simply replace system_clock with steady_clock. Here’s the simplified version:

#include <chrono>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

auto start = std::chrono::steady_clock::now();

// ... Code to be measured goes here

auto end = std::chrono::steady_clock::now();

// Time calculation works exactly like system_clock

using namespace std::literals;

std::cout << "ms: " << (end - start) / 1ms << std::endl;

return 0;

}

The time calculation logic is identical to the system clock method.