What Are MSRs (Model-Specific Registers)?

MSRs (Model-Specific Registers) are specialized registers designed for various experimental functions, including debugging, program execution tracing, computer performance monitoring, simplified software programming, and power control.

What Are MSRs?

The concept of MSRs can be elusive, so this section only covers their external aspects—such as descriptions and related instructions—before expanding further. By the end of this article, you should have a clear understanding.

MSRs are a set of registers primarily intended for use by the operating system or executive processes (i.e., code running at privilege level 0). The number and functionality of these registers may vary by processor model.

Virtually all MSRs handle system-related functions and are inaccessible to application programs. Reading and writing MSRs requires the WRMSR and RDMSR system instructions—with one exception: the TSC (Time-Stamp Counter) covered in this series, which can also be read via instructions like rdtsc.

Why Were MSRs Designed?

Why design such registers? They are quite different from common general-purpose registers like EAX.

To understand this, we first need to look at the origin of MSRs. Starting with the 80386 processor, Intel introduced “experimental” features in each new generation of CPUs—features that might not be retained in future processors. This posed a problem: instructions tied to these features could become obsolete.

For example, suppose a new processor generation adds several test-function registers, along with a variant of the mov instruction (let’s call it movx) to read them. If subsequent processors discard these test registers, the movx instruction becomes useless. Programs or compilers using movx would then require rewriting, increasing development effort and compatibility challenges.

To solve this issue, starting with Pentium processors, Intel introduced the WRMSR and RDMSR instruction pair to access both current and future “model-specific registers.” For instance, to read a register related to a test feature, you don’t need to worry about the specific instruction for that register—instead, you use RDMSR to read the register associated with the test feature model. The low-level implementation of the read operation is handled by RDMSR itself. This avoids the problem of instructions becoming obsolete when registers are phased out.

If you search for MSRs in the Intel SDM (Software Developer’s Manual), you’ll find they are consistently associated with experimental functionalities. Additionally, the entire Volume 4 of the manual is titled Model-Specific Registers, highlighting the importance of this technology.

This abstraction may feel similar to high-level programming languages, leading some to refer to MSRs as “virtual registers.” However, MSRs are physical registers—their underlying hardware implementation may change between processor generations, giving them a somewhat “virtual” feel due to the abstraction layer.

You might wonder: If application programs can’t access MSRs, how can WRMSR and RDMSR read/write them?

Except for the TSC (which can be read via rdtsc), accessing MSRs requires setting the ECX register to the target MSR’s address, using RDMSR to transfer the MSR’s value to the EDX:EAX register pair, and then reading EAX and EDX with instructions like mov. Direct access to MSRs via mov or its variants is not allowed.

For details on reading the TSC with rdtsc, see my article: How to Measure Execution Time with rdtsc and C/C++: Using Inline Assembly and Retrieving CPU TSC Clock Frequency. This article uses inline assembly and serves as a practical example to aid understanding.

What Are Architectural MSRs?

Let’s consider another question: We’ve addressed the risk of instruction obsolescence, but what if an entire model is discontinued? As technology evolves, some technologies may be abandoned, leading to obsolete models.

There’s no magic solution like MSRs for this scenario—instead, it relies on conventions and practices.

According to Intel’s documentation: If an MSR is classified as an Architectural MSR, it is expected to persist in future processor generations. Non-architectural MSRs, however, may be deprecated. The responsibility for adapting falls to developers.

A subset of MSRs and their associated bit fields that will remain unchanged across future processor generations are known as “Architectural MSRs.” For historical reasons (dating back to Pentium 4 processors), these Architectural MSRs are prefixed with IA32_.

Names/Addresses

Each MSR has a unique name and address. For a complete list, refer to Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Volume 4: Model-Specific Registers—the entire 500+ page volume is dedicated to listing MSRs.

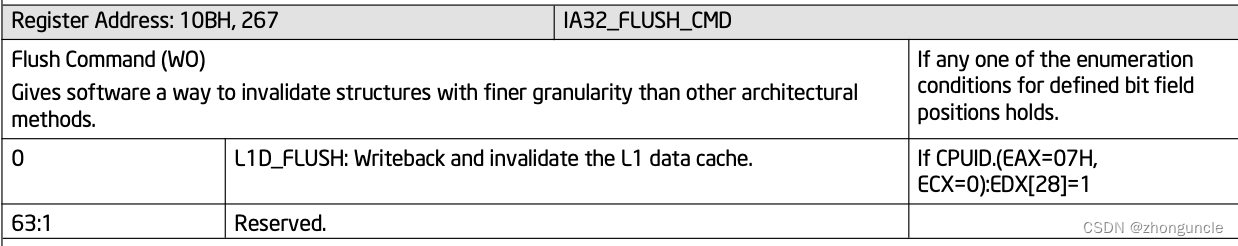

The image below shows a mapping between an MSR address and its Architectural MSR name:

The MSR address range from 4000000H to 4000FFFFH is designated as a specially reserved range. No existing or future processors will use any MSRs in this range for functional implementation.

I hope these will help someone in need~

References

- Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer Manuals: Official Intel processor documentation that details MSRs and includes an extensive list of registers.

- Model-specific register - Wikipedia: While the Wikipedia entry itself is not highly detailed (compiled based on community research), its accompanying references are valuable—worth checking out.