How to Measure Execution Time with rdtsc and C/C++: Using Inline Assembly and Retrieving CPU TSC Clock Frequency

This article is primarily an experimental exploration and intellectual exercise—a preliminary attempt to study implementations of time measurement and the use of inline assembly and assembly functions in C/C++. Unless you have specific use cases, do not use assembly instructions to implement this functionality. The “Further Reading” section lists alternative methods that do not require inline assembly.

I wrote this article because while researching for High-Precision Time Measurement in C/C++ on Windows: A Guide to QPC (QueryPerformanceCounter), I discovered insights into how time measurement works. Out of curiosity, I conducted research and practical experiments on this topic.

Regarding platforms and systems: this article only tests on X86-based macOS. However, since we use inline assembly (not kernel-level system calls), the macOS approach should theoretically work on Linux—though I have not tested this (I lack access to an X86 Linux device).

If you want to implement this on Windows:

- Import

intrin.hand use__rdtsc()and__cpuid()(these intrinsic functions are equivalent to most of the inline assembly in this article). - Avoid inline assembly on Windows: Visual Studio’s inline assembly is far more complex than GCC/Clang’s. For compatibility, Microsoft’s intrinsic functions are the better choice. While this article does not provide Windows-specific code, the “Further Reading” section includes resources to help you implement it yourself.

I originally planned to cover Windows, but omitted it for brevity. Overly long blog posts are inconvenient for both readers and authors (a personal preference).

Core Concept

The time measurement approach in this article works by:

- Calculating the difference between two TSC (Time-Stamp Counter) readings.

- Dividing the difference by the TSC frequency to get the elapsed time.

The timing error of this method mainly depends on the quality of the crystal oscillator—similar to clock(), but far more complex. Unlike clock() (which uses a simple 1 MHz denominator), the TSC frequency is not a fixed value.

On x86 architectures, the most common timer is the CPU’s TSC. However, due to BIOS settings, TSC support, and other factors, popular timing functions typically use multiple timers to eliminate errors. This article does not go that far—we only use TSC counts and frequency for timing.

Additionally, after reviewing numerous domestic and international articles, I noticed a significant shift in x86 TSC technology around 2014 (personal observation). Early blogs, articles, and code describe methods and issues that are almost unrecognizable today. This timeline aligns with Intel’s official documentation on processor updates from that period.

Many early articles covered TSC because assembly was a popular programming technique back then—widely used and studied. Today, high-level languages cover nearly all development scenarios, and assembly has faded from view. As a result, fewer people research assembly or low-level infrastructure implementations, leading to fewer such articles.

Implementation with Inline Assembly

Pure assembly is rarely used in daily development, so we use inline assembly to reduce complexity and improve readability. Inline assembly also preserves the structure of assembly code, making it easy to convert to pure assembly if needed later.

Step 1: Verify TSC Exists and Is Invariant

First, confirm two critical points:

- The CPU has a TSC.

- The TSC is invariant (its frequency does not change with Turbo Boost, overheating, core switching, etc.).

If the TSC is variable, this method cannot reliably measure time. If no TSC exists, further steps are unnecessary.

How to Verify TSC Existence

Check if CPUID.1:EDX.TSC[bit 4] = 1:

- Initialize

EAX = 0x1for theCPUIDinstruction. - Check bit 4 of the

EDXregister returned byCPUID. A value of1means TSC is supported.

How to Verify Invariant TSC

Check if CPUID.80000007H:EDX.InvariantTSC[bit 8] = 1:

- Initialize

EAX = 0x80000007for theCPUIDinstruction. - Check bit 8 of the

EDXregister returned byCPUID. A value of1means invariant TSC is available.

Inline assembly code:

#define BIT(nr) (1UL << (nr)) // Macro to check bit nr (LSB = rightmost bit)

static inline void isTSC(void)

{

uint32_t a=0x1, b, c, d;

asm volatile ("cpuid"

: "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d)

: "a" (a), "b" (b), "c" (c), "d" (d)

);

if ((d & BIT(4))) {

printf("TSC exist!\n");

}

a=0x80000007;

asm volatile ("cpuid"

: "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d)

: "a" (a), "b" (b), "c" (c), "d" (d)

);

if ((d & BIT(8))) {

printf("Invariant TSC available!\n");

}

}

Key Notes on the Code:

static inline: Used to improve performance, but may sometimes reduce performance (depending on the compilation pipeline). Use it at your discretion.- Inline assembly structure:

asm volatile ("cpuid" : "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d) // Output operands (registers → variables) : "a" (a), "b" (b), "c" (c), "d" (d) // Input operands (variables → registers) );- The assembly is split by colons (

:) into up to three parts: instructions, outputs, inputs (outputs first, then inputs). a/b/c/drepresent theeax/ebx/ecx/edxregisters (compatible across 32/64-bit architectures).

- The assembly is split by colons (

- Always declare all registers (even if unused): Omitting registers like

ebx/ecxon macOS may cause memory access errors (e.g., when checking invariant TSC).

Sample output:

TSC exist!

Invariant TSC available!

Important: This code uses print statements for demonstration. In production code, return a boolean value to check TSC availability (implemented in the full code below).

Step 2: Read TSC Count with rdtsc

The TSC value is read via the rdtsc instruction, which loads the 64-bit TSC from the MSR (Model-Specific Register) into the EDX:EAX register pair:

EDX: High 32 bits of the TSC.EAX: Low 32 bits of the TSC.

Wrapper function with inline assembly:

static inline unsigned long long rdtsc(void)

{

unsigned long long low, high;

asm volatile ("rdtsc" : "=a" (low), "=d" (high));

return low | (high << 32); // Combine high/low into 64-bit value

}

Test the function:

printf("%llu\n", rdtsc());

printf("%llu\n", rdtsc());

Sample output:

13207359930699

13207359964314

If you’re curious about MSR, check out my blog post: What Are MSRs (Model-Specific Registers)?

Step 3: Get TSC Frequency via cpuid

Obtaining the TSC frequency is the most challenging part of this article—direct access to TSC values is restricted for security/readability reasons. We need to calculate it using CPUID data.

Simplified Example Code

First, here’s the code (we explain it in detail below):

static inline uint32_t tsc_freq(void)

{

uint32_t a=0x15, b, c=0, d;

asm volatile ("cpuid"

: "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d)

: "0" (a), "1" (b), "2" (c), "3" (d)

);

return b/a*24000000; // 24000000 = core crystal clock (adjust for your CPU)

}

How TSC Frequency Is Calculated

The process is complex because TSC frequency calculation differs between old and new CPUs:

Many articles/books get TSC frequency via the kernel file

/sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/tsc_freq_khz. This article does not use this method (see “References/Further Reading” for resources on this approach).

Step 3.1: CPUID.15H Return Values

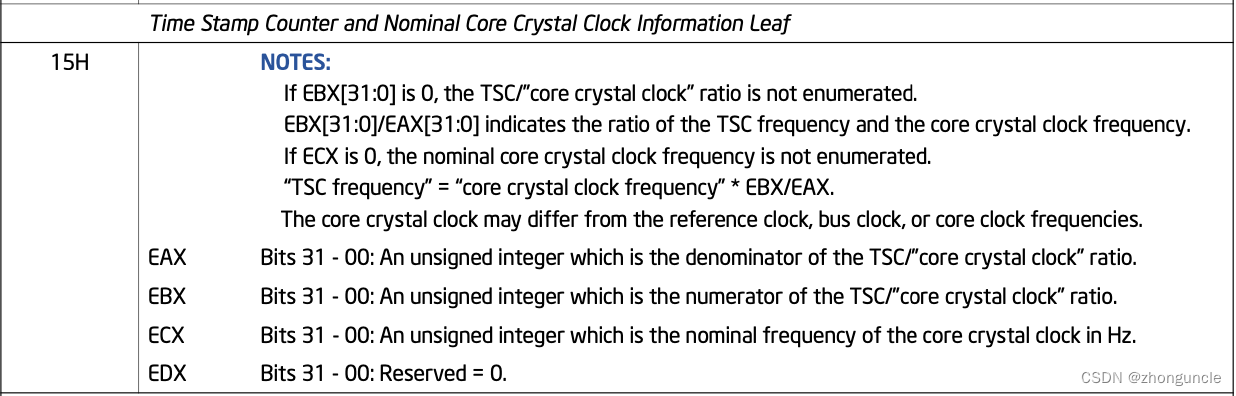

From Intel’s Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer Manuals (April 2021):

Table numbers may vary across manual versions.

The

CPUIDinstruction returns processor identification/feature info in theEAX,EBX,ECX, andEDXregisters. The output depends on theEAXvalue (and sometimesECX) before execution.

In our code:

EAX = 0x15(15H)ECX = 0x0

Step 3.2: Core Crystal Clock Frequency

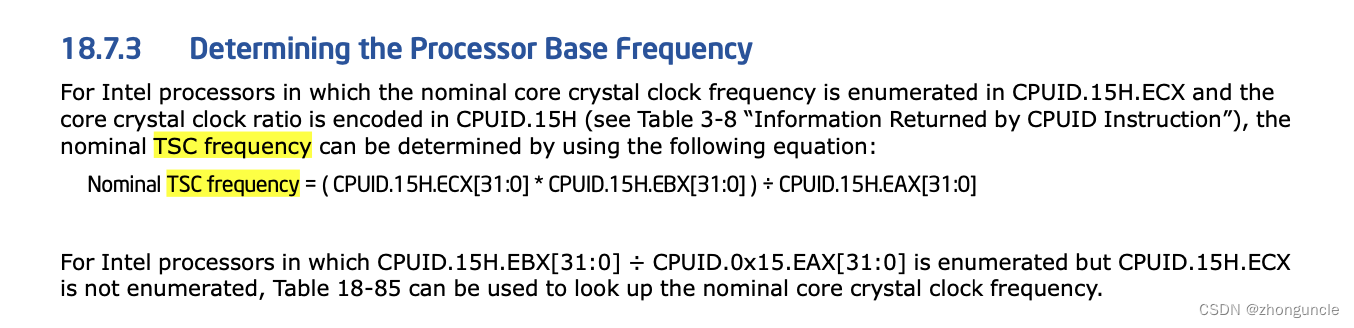

From Section 18.7.3 of the Intel manual:

Key takeaways from the diagram:

- The nominal core crystal clock frequency is listed in

ECX(fixed frequency, synchronized with the system clock).- Most modern CPUs (Skylake and later) or CPUs with scaled frequencies no longer list this value in

ECX. - If

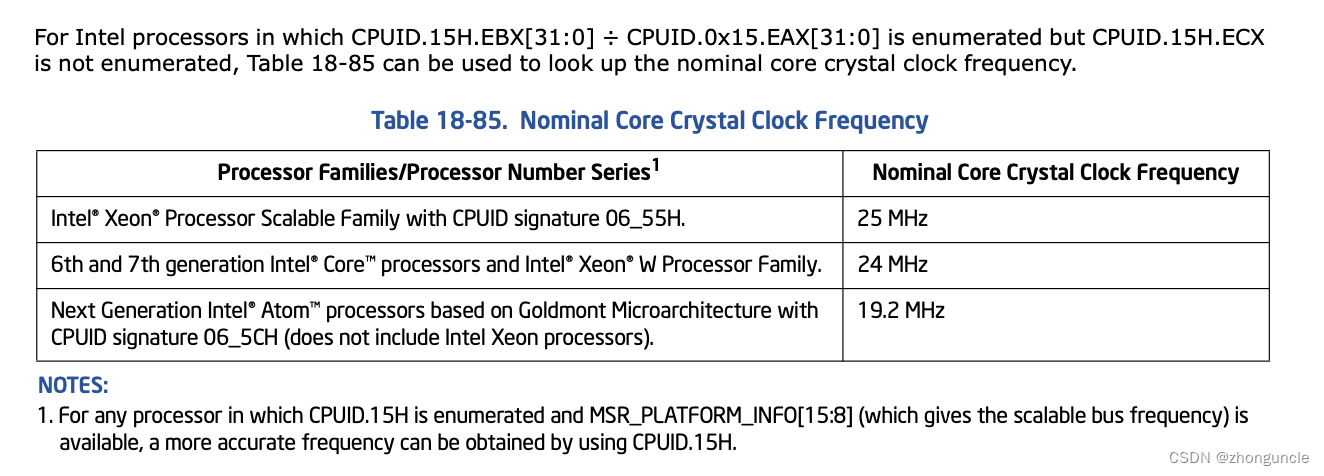

ECX = 0, use Table 18-85 to calculate TSC frequency.

- Most modern CPUs (Skylake and later) or CPUs with scaled frequencies no longer list this value in

CPUID.15Hreturns the core crystal clock ratio (numerator/denominator).- The formula calculates the nominal TSC frequency.

Table 18-85 (for ECX = 0):

Step 3.3: Calculate TSC Frequency (Practical Example)

Test on an Intel i5-8500B:

CPUID.15Hreturns:eax=2,ebx=250,ecx=0,edx=0- Ratio:

ebx/eax = 250/2 = 125 - Core crystal clock (from Table 18-85):

24 MHz - TSC frequency =

24 MHz × 125 = 3000 MHz(matches the i5-8500B base frequency)

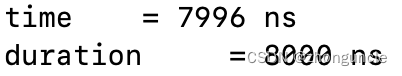

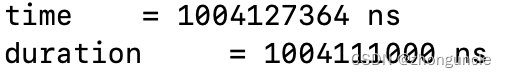

Sample test results (time = TSC-calculated time; duration = clock_gettime() time):

Multiple tests show a maximum error of less than 500 ns (results may vary by machine and environment).

Step 3.4: CPUID Signature

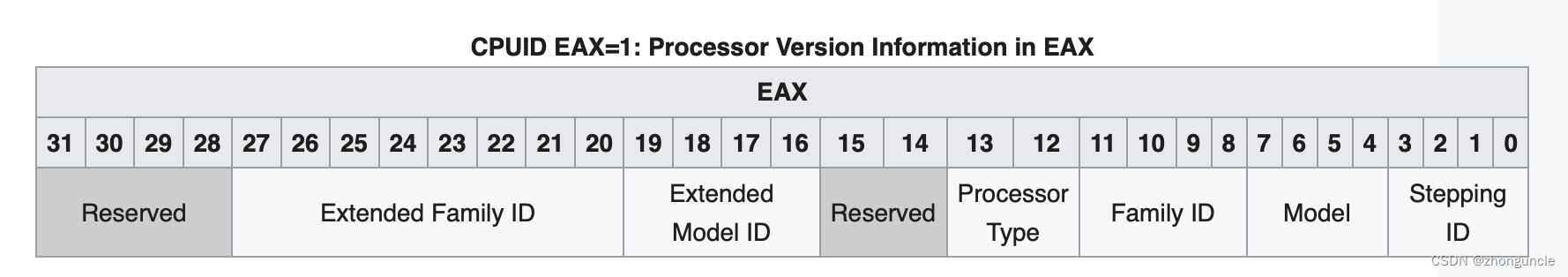

To determine the core crystal clock frequency (when ECX = 0), you need the CPUID signature (returned in EAX when EAX = 0x1 for CPUID):

You only need the Model portion of the signature (not the full EAX value) for two reasons:

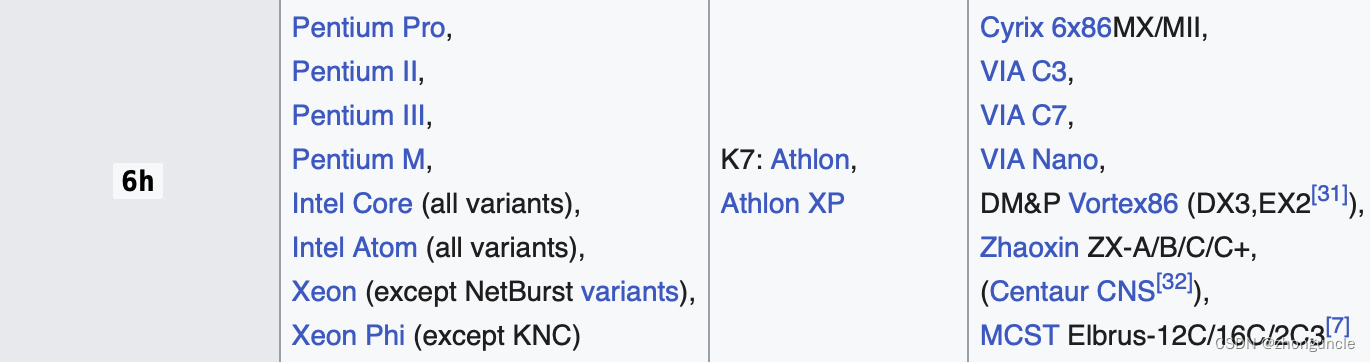

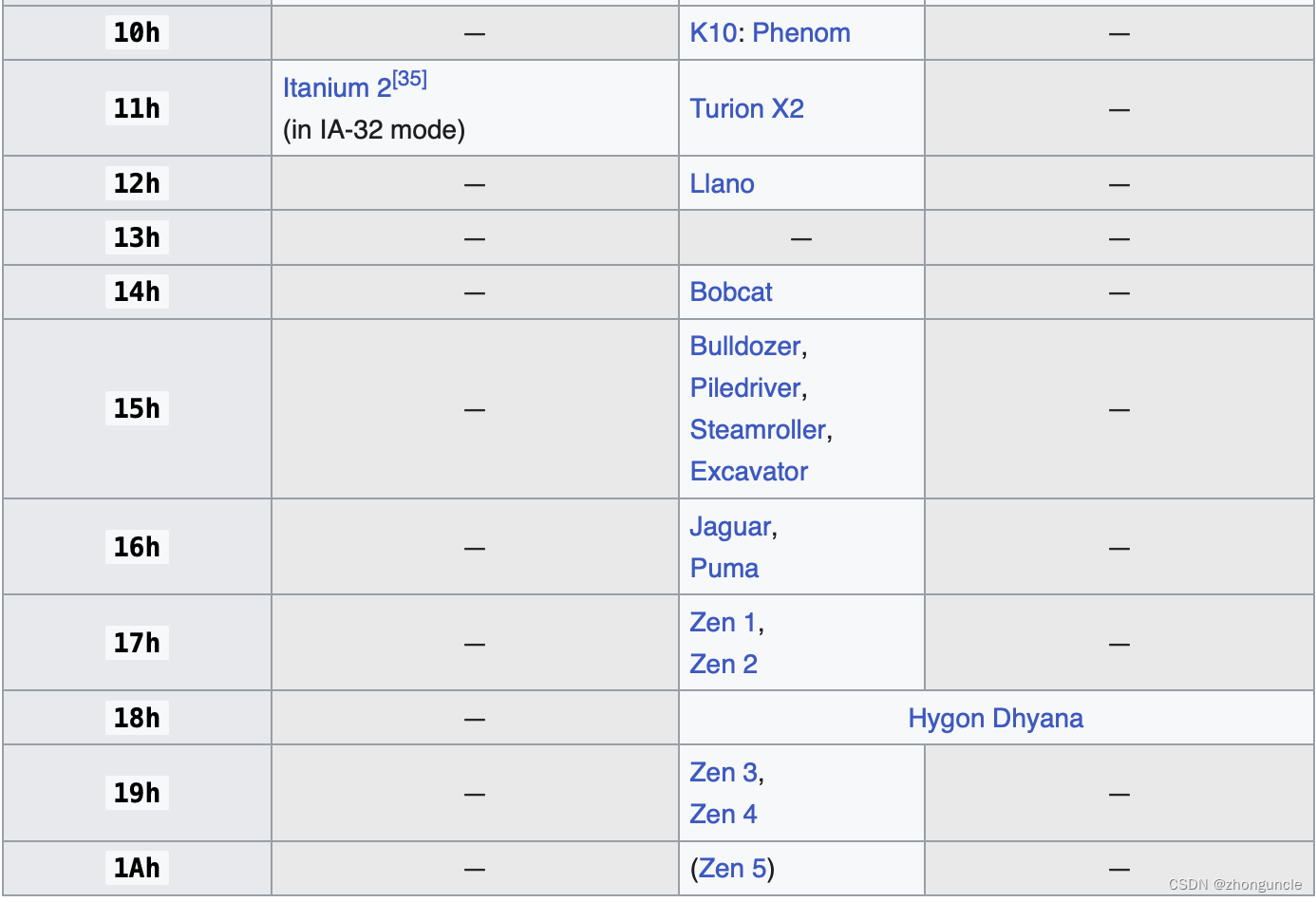

- Most modern Intel Core/Xeon CPUs use a Family ID of

06H(hex), which covers the processors in Table 18-85. - Only CPUs with Family ID

06Hlack core crystal clock info inECX(all others list it directly).

Family ID 06H includes:

Processors using Extended Family ID:

Step 3.5: Extract the CPU Model

Code to get the CPU Model (combines Base Model and Extended Model):

static inline unsigned int cpu_model(void)

{

uint32_t a=0x1, b, c, d;

asm volatile ("cpuid"

: "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d)

: "a" (a), "b" (b), "c" (c), "d" (d)

);

uint32_t model = (a>>4)&0b1111; // Extract Base Model (bits 7-4)

uint32_t extend_model = (a>>16)&0b1111; // Extract Extended Model (bits 19-16)

return (extend_model<<4) | model; // Combine into full Model ID

}

Warning: Do not use

a&0b11110000—this includes extra bits (bits 3-0) that you do not need.

Sample output (i5-8500B):

9e

Important Considerations

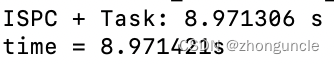

Multicore Parallel Task Timing

Some articles claim TSC cannot measure multicore parallel tasks. This is likely due to:

- Kernel implementation differences on certain systems.

- Early CPU limitations.

In modern CPUs (with invariant TSC), this is no longer an issue:

- I tested with multicore parallel tasks written in ISPC.

- TSC-based timing results are nearly identical to

clock_gettime().

Sample result:

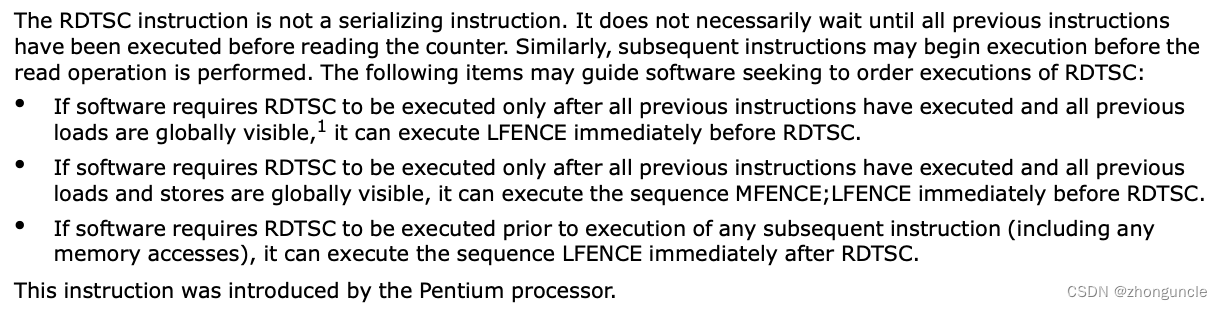

Instruction Execution Order

Some developers worry about rdtsc being delayed or reordered by the CPU. From Intel’s documentation:

Key points:

RDTSCis not a serializing instruction: It does not wait for all prior instructions to complete before reading the counter.- Subsequent instructions may execute before

RDTSCfinishes reading the counter. - The behavior depends on your application’s requirements (three scenarios are covered in the documentation).

Full Code

We use C++ standard library (iostream) for convenience (supports uint32_t, bool, etc.). For pure C, replace with <stdio.h>/<stdint.h> and adjust the code accordingly.

I have organized both C and C++ versions in TSC_Timer - GitHub ZhongUncle (clone and run directly).

Full C++ code:

#include <iostream>

#define BIT(nr) (1UL << (nr)) // Check bit nr (LSB = rightmost bit)

static inline unsigned long long rdtsc(void)

{

unsigned long long low, high;

asm volatile ("rdtsc" : "=a" (low), "=d" (high));

return low | (high << 32);

}

static inline bool isTSC(void)

{

uint32_t a=0x1, b, c, d;

asm volatile ("cpuid"

: "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d)

: "a" (a), "b" (b), "c" (c), "d" (d)

);

if ((d & BIT(4))) {

// TSC exists

a=0x80000007;

asm volatile ("cpuid"

: "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d)

: "a" (a), "b" (b), "c" (c), "d" (d)

);

if ((d & BIT(8))) {

// Invariant TSC available

return true;

}

} else {

// TSC does not exist

return false;

}

return false;

}

static inline unsigned int cpu_model(void)

{

uint32_t a=0x1, b, c, d;

asm volatile ("cpuid"

: "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d)

: "a" (a), "b" (b), "c" (c), "d" (d)

);

uint32_t model = (a>>4)&0b1111;

uint32_t extend_model = (a>>16)&0b1111;

return (extend_model<<4)|model;

}

static inline unsigned long tsc_freq(void)

{

uint32_t model = cpu_model();

uint32_t a=0x15, b, c, d;

asm volatile ("cpuid"

: "=a" (a), "=b" (b), "=c" (c), "=d" (d)

: "0" (a), "1" (b), "2" (c), "3" (d)

);

if (c != 0) {

return b / a * c;

}

if (model == 0x55) {

return b / a * 25000000;

}

if (model == 0x5c) {

return b / a * 19200000;

}

return b/a*24000000;

}

int main(int argc, const char * argv[]) {

// Check for reliable TSC

if (!isTSC()) {

printf("TSC is not exist or variant!");

return 1;

}

// Get TSC frequency

unsigned long freq = tsc_freq();

// Verify with clock_gettime

struct timespec start;

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &start);

// Get start TSC count

uint64_t rdtsc1 = rdtsc();

// Test code for timing

for (int i=0; i<100; i++) {

std::cout << "Hello, World!\n";

}

// Get end TSC count

uint64_t rdtsc2 = rdtsc();

struct timespec end;

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &end);

// Calculate elapsed time (nanoseconds)

double time = (double)(rdtsc2-rdtsc1)/(double)freq*1e9;

// Print results

printf("clock\t = %llu cycles\n", rdtsc2-rdtsc1);

printf("freq\t = %lu Hz\n", freq);

printf("TSC time = %.0f ns\n", time);

// Calculate clock_gettime result (nanoseconds)

double duration = (double)(end.tv_nsec-start.tv_nsec) + (double)(end.tv_sec-start.tv_sec)*1e9;

printf("duration = %.0f ns\n", duration);

return 0;

}

I hope these will help someone in need~

Further Reading

- How to get the CPU cycle count in x86_64 from C++? - Stack Overflow: Top answer explaining

__rdtscfor Linux/Windows. - __rdtsc - Microsoft Learn: Official docs for Microsoft’s

__rdtscintrinsic. - TSC Frequency For All: Better Profiling and Benchmarking - Trail of Bits: Uses

/sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/tsc_freq_khzto get TSC frequency. - Getting TSC rate from x86 kernel - Stack Overflow: High-level methods to get TSC frequency.

- Using and Preserving Registers in Inline Assembly - Microsoft Learn: Windows inline assembly best practices.

- How to do cpuid and rdtsc on 32 bit and 64 bit Windows - Stephen Kellett: Windows-specific

cpuid/rdtscimplementation.

References

I encountered many misleading resources during my research—here are the most reliable ones:

- Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer Manuals: Official Intel docs (very long—read the overview first, then only updates).

- 6.48.2 Extended Asm - GCC: Official GCC inline assembly docs.

- Inline Assembly/Examples - OS Dev: Practical inline assembly examples.

Recommended to read these 4 together:

- CPUID — CPU Identification - felixcloutier: Online version of Intel SDM (CPUID details).

- CPUID - OS Dev: Detailed

cpuidexamples (no explanations). - CPUID - Wikipedia: Quick reference for CPUID families/registers.

- Query CPUID with Inline Assembly - Jack Henschel’s Blog: Bachelor’s thesis summary (better examples than OS Dev).

Other key resources:

- RDTSC — Read Time-Stamp Counter - felixcloutier:

rdtscinstruction details. - Function asm volatile(“rdtsc”); - Stack Overflow:

rdtscinline assembly discussion. - TSC frequency computation - Intel Community: TSC frequency precision issues on early CPUs.