SMA (3/3) KMP (Knuth–Morris–Pratt) string matching algorithm

KMP (Knuth–Morris–Pratt) String Matching Algorithm

The KMP (Knuth–Morris–Pratt) string matching algorithm is well-suited for finding a single match. For multiple matches, an improved version of Rabin-Karp is a better choice.

This article is structured as follows (corresponding to the sidebar directory):

- Why KMP is so hard to understand across different resources, along with key differences and considerations;

- A brief introduction and characteristics of the KMP algorithm;

- How KMP works;

- The working logic of KMP;

- How the critical

nextarray in KMP is calculated; - Why the

nextarray can compute the appropriate offset; - Complete code.

The reason I explain “how it works” before “working logic” is to let you first see KMP in action, making it easier to understand the underlying logic. Do not force yourself to master the “How KMP Works” section right away. I know many blog examples are subpar and incomplete. (The example in the original paper perfectly covers the three required scenarios—it’s excellent, just a bit lengthy.)

I provide numerous examples in subsequent sections, which can also aid memorization. After reading these, you’ll understand the original paper’s example at a glance, saving time.

Some Rants

KMP is a masterpiece, and its three independent inventors are all extraordinary:

- Donald Knuth: Author of TAOCP and TeX, recipient of the 1974 Turing Award.

- James H. Morris: Emeritus Professor of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University.

- Vaughan Pratt: Knuth’s student, who completed his Stanford PhD in 20 months and became an emeritus professor at Stanford University in 2000.

This background (especially Knuth’s involvement) makes the algorithm’s underlying principles hard to grasp. It took me an entire day to understand what KMP is and how the paper relates to the explanations in various textbooks—making the learning process somewhat comical.

When learning KMP, I found that domestic textbooks introduce it as an improvement on the naive algorithm, adding a next array (Partial Match table, PM) that records the length of the longest equal prefix and suffix for each position in the substring. I don’t know if you understood this explanation, but I certainly didn’t.

I then discovered that Introduction to Algorithms frames KMP as an improvement on finite automata, also mentioning prefix calculation, with a strong mathematical focus. I grasped the general idea but had no clue how to implement it in code.

Neither explanation satisfied me.

Online blogs and code implementations either parrot domestic textbooks, reference Introduction to Algorithms, or provide no explanation at all—yielding the same confusing results.

Finally, I read KMP’s original paper and realized why domestic textbooks and Introduction to Algorithms fail to clarify the logic: the algorithm is incredibly ingenious and difficult to explain simply. Additionally, while Knuth is now a renowned figure, this paper was written early in his career, with immature writing techniques and no fixed structure (academic papers lacked standard formatting back then), resulting in a disorganized presentation.

The funniest part? There’s no unified method for calculating KMP across resources—this is why you’ll never see exams test next array calculation, as it’s not unique. How inconsistent is it?

- Whether character numbering starts at 0 or 1.

- Whether

nextarray numbering starts at 0 or 1. - Whether

next[0]is 0 or 1.

Do the permutations: theoretically, a single pattern can have 8 versions of the test array (fewer in practice—about 3–4, since character and array numbering are correlated). Each version uses a slightly different calculation method but yields the same final result. So if you’re studying for exams, memorize your textbook’s method and don’t waste time researching the algorithm itself like I did.

This article uses the original paper’s method for calculating KMP’s test array (string and next numbering start at 1). However, the code follows C conventions (string and next numbering start at 0).

What is the KMP Algorithm?

Most string matching algorithms consist of two phases: preprocessing and matching. Preprocessing involves processing the pattern string to speed up subsequent matching.

However, during matching (whether with the naive algorithm or finite automata), mismatches occur, requiring “backtracking”—rechecking the same segment multiple times.

“Backtracking” refers to moving backward in the pattern string, not the text string being matched.

For example, when matching BCD in ABCBCD, a mismatch occurs at the second B:

- The naive algorithm resumes comparison at the first

C(since the previousBfailed), and the pattern string restarts matching from its first element (B). - Finite automata stay at the current

Band attempt to matchCnext, but this involves a backtracking operation that ultimately keeps it at the same position.

The former restarts matching from the beginning of the pattern string every time, while the latter sometimes avoids full restarts—making it slightly faster.

| Algorithm | Preprocessing Time | Matching Time |

|---|---|---|

| Naive Algorithm | $0$ | $O((n-m+1)m)$ |

| Finite Automaton | $\Theta(m|\sum|)$ | $\Theta(n)$ |

If you read the previous article, you know the finite automaton’s preprocessing phase is quite complex—it not only determines the next state in a table but also sets the backtracking position. So is it possible to eliminate backtracking entirely? In other words, ensure each character in the text string is matched only once.

This is exactly what KMP does. Compared to traditional methods, it eliminates the backtracking phase by directly shifting the pattern string to the right, avoiding repeated character comparisons.

Additionally, KMP only requires a one-dimensional array (length = pattern string length) instead of a two-dimensional array (size = pattern string length × number of possible input values), resulting in significant improvements in both time and space efficiency.

Time efficiency improves because the preprocessing phase requires less work, naturally reducing computation time.

| Algorithm | Preprocessing Time | Matching Time |

|---|---|---|

| Naive Algorithm | $0$ | $O((n-m+1)m)$ |

| Rabin-Karp | $\Theta(m)$ | $O((n-m+1)m)$ |

| Finite Automaton | $\Theta(m|\sum|)$ | $\Theta(n)$ |

| KMP | $\Theta(m)$ | $\Theta(n)$ |

Like other string matching algorithms, KMP’s preprocessing phase is the most critical and complex part. Shifting the pattern string to the right is simple, but calculating the correct shift distance is not.

How KMP Works

The original paper’s example is used to explain how KMP works.

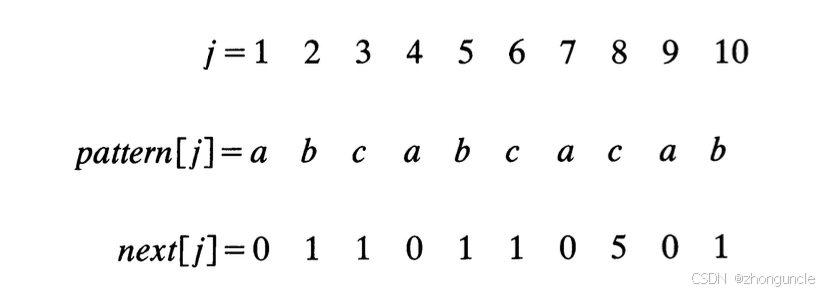

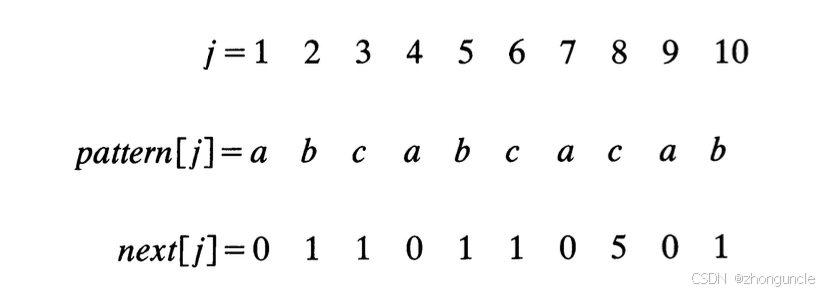

The image below shows the pattern string and corresponding next array elements:

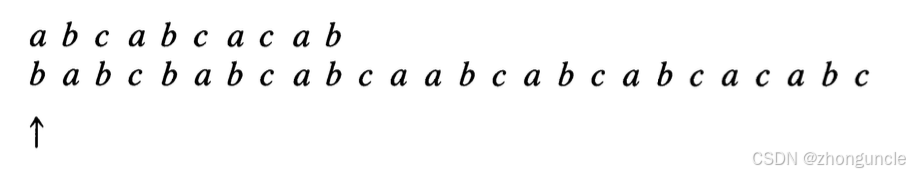

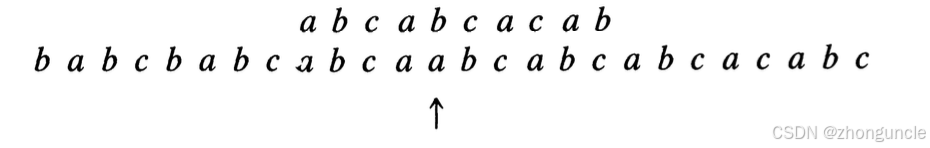

In the image below: the top row is the pattern string, the middle row is the text string, and the bottom row indicates the character being checked:

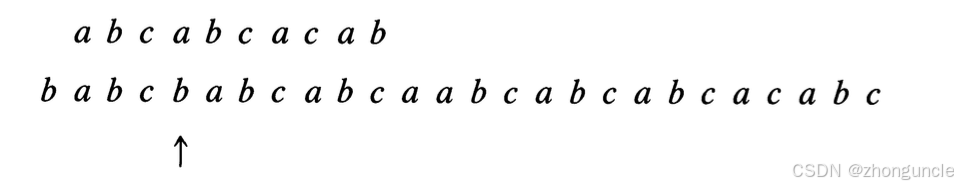

As shown, the first character mismatches, so the pattern string is shifted right by $1-\text{next}[1] = 1$ position. Since $\text{next}[1]=0$, matching restarts from the beginning. A mismatch occurs at the 4th character:

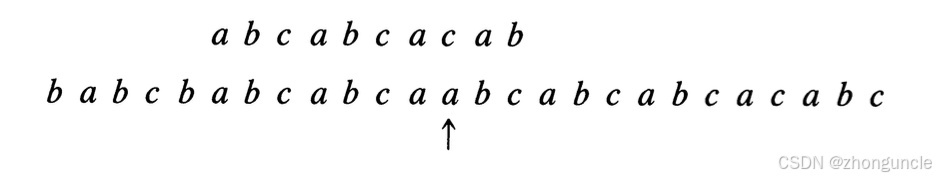

At this point, $\text{next}[4]=0$, so $4-\text{next}[4] = 4-0 = 4$—shift right by 4 positions, and restart matching from the beginning. Another mismatch occurs at the 8th character:

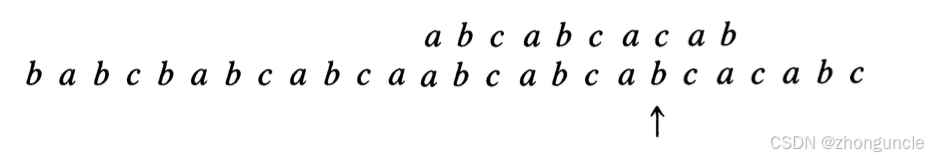

Now, $\text{next}[8]=5$, so $8-\text{next}[8] = 8-5 = 3$—shift right by 3 positions, and resume matching from the 5th character.

If you’re confused why we only shift 3 positions here, the section “Why $\text{index}-\text{next}[\text{index}]$ is the pattern offset” will explain this.

A mismatch occurs at the 5th character this time:

Here, $\text{next}[5]=1$, so $5-\text{next}[5] = 5-1 = 4$—shift right by 4 positions, and restart matching from the first character. Another mismatch occurs at the 8th character:

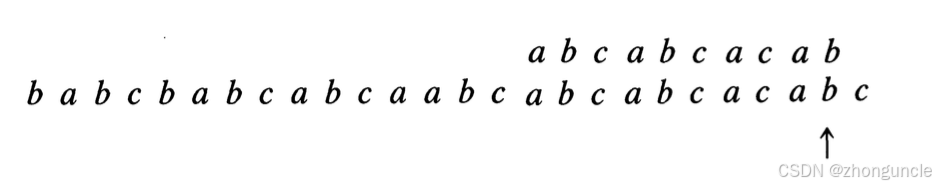

Shift right by 3 positions and resume matching from the 5th character. This time, a full match is achieved:

KMP Working Logic

KMP uses the same algorithm for both preprocessing and matching—a detail mentioned in both Introduction to Algorithms and the original paper.

The only difference is:

- Preprocessing involves matching the pattern string against itself;

- Matching involves matching the pattern string against another text string.

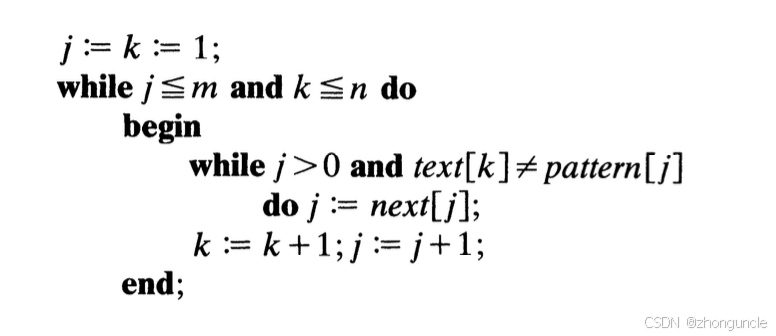

The algorithm structure is as follows:

Place the pattern on the left

while the pattern is not fully matched and the text string is not exhausted

while the pattern character does not match the current text character

shift the pattern right to the appropriate position

move to the next character in the text string

The code structure is shown below:

What does “shift the pattern right to the appropriate position” mean? This relies on the following equation:

k = p + j

- $k$ = index of the text string;

- $j$ = index of the pattern string;

- $p$ = a value that satisfies the equation (essentially the offset, as seen by rearranging to $p=k-j$).

We typically fix $k$ and $p$ to match the string—once these two are determined, the third value is known.

This equation is the core idea of KMP. KMP’s correctness is proven using this equation, and it is also used to calculate the next array. The section “Why $\text{index}-\text{next}[\text{index}]$ is the pattern offset” will explain why this is KMP’s core.

Proving an algorithm’s correctness means verifying it mathematically—ensuring it is logical and rigorous. Even extensive testing with examples cannot guarantee no errors otherwise.

How KMP’s next Array is Derived

From the above process, you can see the next array is the key to KMP. So how is this array calculated?

Let’s walk through the calculation of the next array for the original paper’s example.

The original paper introduces a function $f[x]$ when calculating next. Recall earlier that KMP uses the same algorithm for preprocessing and matching (only the target differs)—this $f[x]$ corresponds to $j$ in the demonstration below.

$f[x]$ is defined for both the text and pattern strings, but when calculating next, both are the pattern string. Do not overcomplicate things by following the paper’s notation—$f[x]$ is included as a comment in the code below and is not required.

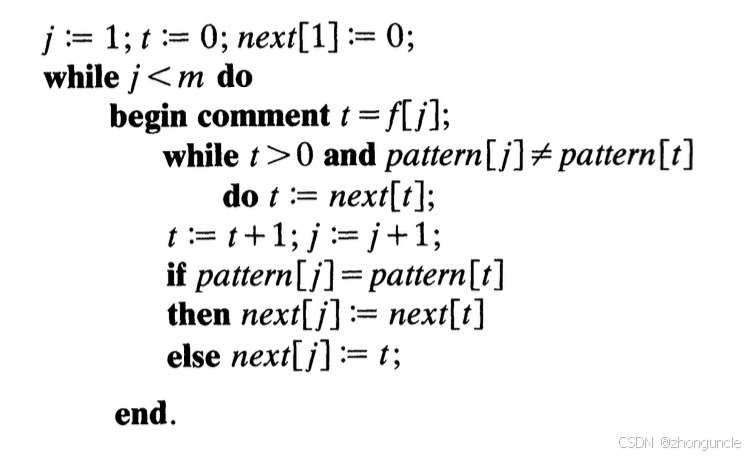

The code structure for calculating next described in the paper is as follows:

This explanation is quite abstract, so let’s use the paper’s example to walk through the steps:

Initial state:

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> By convention, the first value is 0 or -1; here we set next[1]=0

(p=text index; k=p+j; j=pattern index)

First match (p=1, k=2, j=1)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> text[p+j] != pattern[j], next[2]=j=1

Second match (p=2, k=3, j=1)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> text[k] != pattern[j], next[3]=j=1

Third match (p=3, k=4, j=1)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> Match found, next[4]=next[j]=next[1]=0

(When matching, only move the check point—do not shift the pattern (p remains unchanged))

Fourth match (p=3, k=5, j=2)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> Match found, next[5]=next[j]=next[2]=1

Fifth match (p=3, k=6, j=3)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> Match found, next[6]=next[j]=next[3]=1

Sixth match (p=3, k=7, j=4)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> Match found, next[7]=next[j]=next[4]=next[1]=0

Seventh match (p=3, k=8, j=5)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> Mismatch, next[8]=j=5

Eighth match (p=8, k=9, j=1)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> Match found, next[9]=next[j]=next[1]=0

Ninth match (p=9, k=10, j=1)

|

text: a b c a b c a c a b

pattern: a b c a b c a c a b -> Mismatch and end of string, next[10]=j=1

This result matches the paper exactly:

In summary:

- If a match is found: only move the check point (do not shift the pattern, so p remains unchanged). Then $\text{next}[k]=\text{next}[j]$.

- If a mismatch occurs (or the string is exhausted): only move the check point (do not shift the pattern, so p remains unchanged). Then $\text{next}[k]=j$.

However, calculating the next array using some textbooks’ methods will yield different values.

For example, calculating based on the number of common prefix/suffix elements:

- For

a: both prefix and suffix are empty sets → value = 0; - For

ab: prefix = {a}, suffix = {b}, intersection is empty → value = 0; - For

abc: prefix = {a, ab}, suffix = {c, bc}, intersection is empty → value = 0; - For

abca: prefix = {a, ab, abc}, suffix = {a, ca, bca}, intersection = {a} → value = 1; - …..

The first few values are already different, but the shift distance and final result remain the same. If you use this method to generate the next array, note that numbering must start at 0 (i.e., j in the image above)—otherwise, errors will occur.

Some textbooks suggest only considering matched characters when calculating shift distance. I find this redundant—proper index handling is more convenient and efficient.

nextval

Another reason I recommend the original paper’s method: some textbooks mention a nextval array for KMP and highlight its advantages, but this is actually the same as the paper’s approach.

Why $\text{index}-\text{next}[\text{index}]$ is the Pattern Offset

Mathematically proving KMP’s correctness is complex (the paper covers this in detail), so I’ll use plain language to explain key points readers may care about.

The

nextarray used here is calculated using the paper’s method—adjust accordingly if you use a different approach.

From the previous section, you’ll see next represents the current index of the pattern string. During matching, we operate on the text string’s index; if we know the pattern string’s index (i.e., next), we can calculate the offset using the earlier equation.

This raises the question: why is the offset from self-matching equal to the offset from pattern matching?

First, let’s verify this with an example: text string = ABABBABC, pattern string = ABABC. The next array calculation process is:

Initial state:

text: A B C -> next[1]=0

pattern: A B C

(p=text index; k=p+j; j=pattern index)

First match (p=1, k=2, j=1)

|

text: A B C

pattern: A B C -> text[p+j] != pattern[j], next[2]=j=1

Second match (p=2, k=3, j=1)

|

text: A B C

pattern: A B C -> text[p+j] != pattern[j], next[3]=j=1

The next results are:

| Index | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Character | A | B | C |

| next | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Assume we initially know nothing about the text string except the pattern string:

text: A B A B B A B C

pattern: A B C

KMP first matches up to the third character (A), where a mismatch occurs. At this point, we know the first three characters of the text string are ABX (X ≠ C, otherwise the match would succeed). Since X ≠ C, it might equal the pattern’s first character (A), so we restart matching at the same position.

Key insight: There’s no need to remember the preceding

AB—reaching position X means the preceding characters matched successfully.

Using the next array: $3-\text{next}[3] = 3-1 = 2$ → shift right by 2 positions. This yields the same result as the manual operation:

text: A B A B B A B C

pattern: A B C

(Write down the subsequent shifts on paper—hands-on practice accelerates learning.)

For the same reason as before: we now know the first five characters of the text string are ABABX (X ≠ C). Since X ≠ C, it might equal the pattern’s first character (A), so we shift to X again:

You may wonder why I said not to remember the initial

ABbut wroteABABXhere.

This is just to indicate positions—would writing..ABXaffect comparing the last three characters withABC? No. This is KMP’s advantage: no redundant backtracking, so no need to “go back” and recheck.

text: A B A B B A B C

pattern: A B C

This time, a mismatch occurs immediately: we know the first six characters of the text string are ABABBX (X ≠ A). This means the substring starting at X cannot match the pattern, so we skip this character:

text: A B A B B A B C

pattern: A B C

A full match is achieved this time. Return index 6 (or 5 if starting from 0).

Now that we’ve confirmed the equality, why are the self-matching and pattern-matching offsets the same?

We can borrow the physics concept of a “frame of reference” to help explain this.

This concept is not my invention—it is mentioned in the original paper (referencing “relative” positions).

There is “movement” within the pattern string itself, and the pattern string as a whole “moves” across the text string. Here, “movement” refers to “shifting right”.

Since “shifting right” is one-dimensional and unidirectional, we can derive a simple transformation:

Absolute coordinate = relative origin + relative coordinate

Here:

- “Relative origin” = the element in the pattern string used for comparison;

- “Relative coordinate” = the offset from self-matching.

Absolute offset = relative origin + relative offset

This formula is exactly the earlier equation:

k = p + j

With this relationship, we can find repeated segments before the mismatched character and shift by the corresponding distance whenever a right shift is needed:

Relative origin = absolute offset - relative offset

Where:

- “Relative origin” = the shift distance of the origin (if the starting point is 0), i.e., the index shift of the text string—in other words, the desired target position.

- “Absolute offset” = the index of the text string;

- “Relative offset” = the index of the pattern string.

Rearranging gives:

p = k - j

This distance depends only on the pattern string—not the text string being matched.

Honestly, I was amazed when I grasped this layer of logic. The ingenuity of this algorithm, conceived by three people fifty years ago, is truly remarkable.

If you still don’t understand, see the “Generating the State Transition Table” section in 「String Matching Algorithm 2/3」Finite Automaton String Matching Algorithm. I provide an example there that explains this concept and may help clarify things.

The core idea is the same— the only difference is that finite automata search for repeated substrings including the current input character, while KMP excludes it.

Complete Code

Earlier, we mentioned preprocessing and matching use the same algorithm with similar code structures. This code is adapted from the paper, with indices modified to start at 0 (per C conventions). The complete C implementation is:

#include <stdio.h>

void getNext(char pattern[], int m, int next[]) {

next[0]=-1;

int j=0, t=-1;

while (j<m) {

while (t>0 && pattern[j] != pattern[t]) {

t = next[t];

}

j++; t++;

if (pattern[t] == pattern[j]) {

next[j]=next[t];

} else {

next[j]=t;

}

}

}

int kmp(char text[], char pattern[], int n, int m, int next[]) {

int j=0, k=0;

while (j<m && k<n) {

while (j>0 && text[k]!=pattern[j]) {

j=next[j];

}

k++;j++;

}

if (j == m) {

return k-j;

}

return -1;

}

int main() {

char text[]="babcbabcabcaabcabcabcabcacabc";

char pattern[]="abcabcacab";

// Note that C strings have a terminator at the end

int n=sizeof(text)/sizeof(char)-1;

int m=sizeof(pattern)/sizeof(char)-1;

int next[m];

for (int i=0; i<m; i++) {

next[i]=0;

}

getNext(pattern, m, next);

int index=kmp(text, pattern, n, m, next);

printf("Match starts at index %d\n", index);

return 0;

}

The output is:

Match starts at index 18

I hope these will help someone in need~

First article: SMA (1/3) Naive and Rabin-Karp - ZhongUncle GitHub Pages

References

Introduction to Algorithms, Chapter 32.

Knuth, Donald; Morris, James H.; Pratt, Vaughan (1977). “Fast pattern matching in strings”. SIAM Journal on Computing.: The original KMP paper.