SMA (1/3) Naive and Rabin-Karp

SMA (String matching algorithms) have always been my weak spot, and I happened to have a need for them recently, so I took the opportunity to catch up.

String matching algorithms primarily involve identifying a substring (pattern, which is sometimes translated as “pattern” in other contexts, hence sometimes called “pattern matching”) within a larger body of text, such as finding a word in a text editor or a specific sequence in a DNA strand.

Structurally, many string matching algorithms consist of two parts: preprocessing and matching.

There is no preprocess in naive matching algorithm.

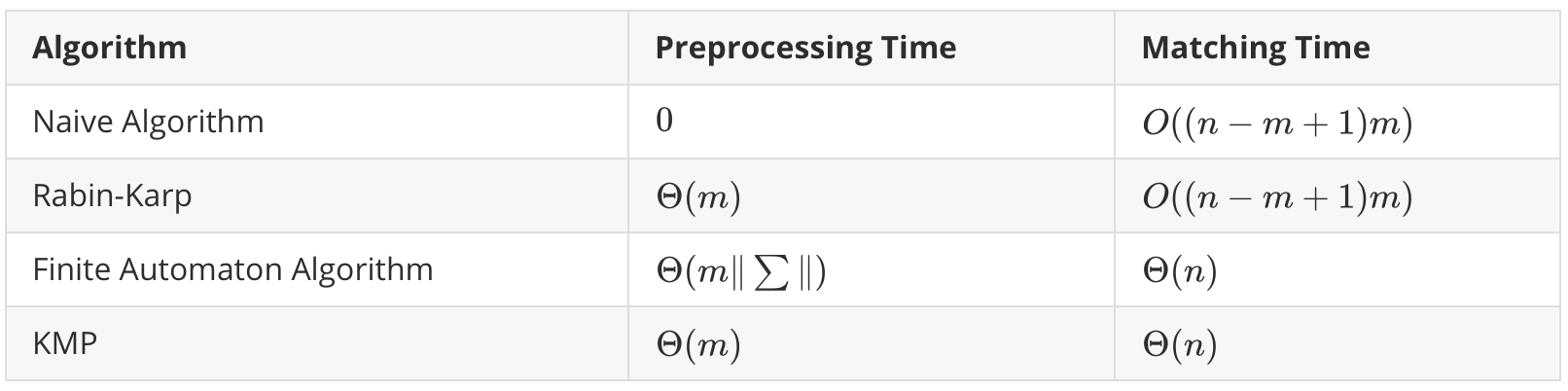

Below are the four matching algorithms listed in “Introduction to Algorithms”, and I’ll start by learning these four. There are certainly more algorithms, but it’s easy to get overwhelmed if you try to learn too much at once.

∑ in the table above represents a set, as the Rabin-Karp algorithm uses equivalence classes from number theory: for example, 1 and 3 yield the same result for mod 2 operation, so 1 and 3 are in the same equivalence class under mod 2.

Preprocessing is done to speed up the matching process. For instance, although the worst-case time for the Rabin-Karp algorithm is the same as the naive matching, in practice, Rabin-Karp is usually much faster.

Naive String Matching Algorithm

This approach is straightforward, checking each character one by one. When a character matches the first character of the substring we’re looking for, we proceed to compare the subsequent characters.

Here’s the C code:

#include <stdio.h>

int naiveMatch(char str[], char partern[], int lenstr, int lenpart) {

int s;

for (s=0;s<=(lenstr-lenpart);s++) {

if (str[s]==partern[0]) {

for (int i=1; i<lenpart; i++) {

if (str[s+i]!=partern[i]) {

break;

} else if (i == lenpart-1) {

printf("%d: %c, %d: %c\n", (s+i), str[s+i], i, partern[i]);

return s;

}

}

}

}

// No match found, return -1

return -1;

}

int main(void) {

// This weird string comes from the initial KMP paper

char str[]="babcbabcabcaabcabcabcabcacabc";

char partern[]="abcabcacab";

// Note that C strings have a termination character, so the length should be reduced by 1

int lenstr=sizeof(str)/sizeof(char)-1;

int lenpart=sizeof(partern)/sizeof(char)-1;

int s = naiveMatch(str, partern, lenstr, lenpart);

// It can also be modified to "start matching from the xth character", and remember to add 1 to s in this case

printf("From %d matching.\n", s);

return 0;

}

The output is:

27: b, 9: b

From 18 matching.

Rabin-Karp Algorithm

The Rabin-Karp algorithm is a bit more complex. If you’re not interested, you can skip it. However, from an interesting perspective, this algorithm is quite intriguing.

It not only uses equivalence classes from number theory but also requires knowledge of some polynomial algorithms; selecting a modulus (i.e., modulo operation) needs to consider machine word length and other issues, which requires developers to have considerable mathematical and computer knowledge.

Of course, this algorithm has its advantages: it’s excellent when you need to match multiple contents, and its efficiency is even higher when combined with Bloom Filter.

Algorithm Logic

The logic of the Rabin-Karp algorithm is:

- Convert the substring to be matched into a number (i.e., an equivalence class, or a hash value);

- Then convert each substring of the string (with the same length as the substring to be matched) into numbers.

- Compare these numbers; parts with the same number might be the same.

- Compare the characters of parts with the same number to prevent false matches (the algorithm can result in different strings producing the same outcome).

For example, 1 and 3 yield the same result for

mod 2operation, both being 1, so 1 and 3 are in the same equivalence class under mod 2. Of course, equivalence classes are a concept from “Introduction to Algorithms”; you can also understand it as a kind of hash function. This is the concept of hashing, although some hash functions have additional operations to handle collisions, which won’t be discussed here.

Obtaining Equivalence Classes (Hash Values)

First, some preprocessing is done to obtain equivalence classes (hash values).

The method to obtain equivalence classes is as follows:

- Represent characters with numbers, such as using 1~26 to represent the 26 English letters, or using ASCII codes, or even UTF-8, Unicode, etc.

- Then use Horner’s rule to generate the value of this string (you can also use other algorithms, just be aware that simple addition is too prone to repetition).

Here, we use 0~25 to represent the 26 English letters to represent characters because we only use English letters. At this time, ∑ = {0,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,…,25,25}.

When choosing a modulus, select a prime number to reduce the number of false matches (the book provides some related analysis; you can check it out if interested). The smallest prime number not less than 26 is 29.

“Introduction to Algorithms” uses 1~10 to represent corresponding numbers, then 13 as the modulus.

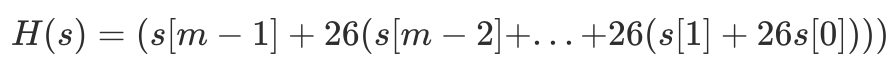

Then, when using Horner’s rule to generate the string’s value, use the following algorithm (m is the length of the matching string):

That is, s[0]x26+s[1] is the value of two characters, and so on, finally taking the result modulo 29.

However, whether to take the modulo at the end or not is actually optional; it just narrows down the result range. Otherwise, sometimes it might exceed the length of a single instruction, which would reduce computational speed.

The generation algorithm is as follows:

for (int i=0; i<lenpart; i++) {

ph = 26 * ph + (partern[i]-'a');

}

ph = ph % 29;

This way, the string ccd results in a value of 1743.

Finding Equivalence Classes with Matching Values

Now we come to the actual matching phase.

However, this is a simple search algorithm, where you can directly compare one by one, which has no technical difficulty.

Determining if It’s a False Match

This is the naive string matching algorithm mentioned earlier, only with significantly reduced workload, as any mismatch at the corresponding index can lead to a false dismissal.

Complete Code

#include <stdio.h>

int RabinKarp(char str[], char partern[], int lenstr, int lenpart, int d, int m) {

/* Preprocessing phase */

int ph=0;

int sh[lenstr - lenpart + 1];

// Set each element of sh[] to 0, to avoid non-zero initial values

for (int i=0; i<(lenstr - lenpart + 1); i++) {

sh[i]=0;

}

// Generate the value of the matching string

for (int i=0; i<lenpart; i++) {

ph = 26 * ph + (partern[i]-'a');

}

ph = ph % 29;

// Generate the value of substrings

for (int i=0; i<=(lenstr-lenpart+1); i++) {

for (int j=0; j<lenpart; j++) {

sh[i] = 26 * sh[i] + (str[i+j]-'a');

}

sh[i] = sh[i] % 29;

}

/* Matching phase */

// Check for matching values

// (This returns the first match found; if you want to match multiple values, you can use a linked list or array to store the indices and then compare them)

for (int i=0; i<=(lenstr-lenpart+1); i++) {

// Check for false matches

if (ph==sh[i]) {

for (int j=0; j<lenpart; j++) {

if (str[i+j]!=partern[j]) {

break;

} else if (j==lenpart-1) {

return i;

}

}

}

}

return -1;

}

int main(void) {

char str[]="babcbabcabcaabcabcabcabcacabc";

char partern[]="abcabcacab";

//C string has a end symbol.

int lenstr=sizeof(str)/sizeof(char)-1;

int lenpart=sizeof(partern)/sizeof(char)-1;

int s = RabinKarp(str, partern, lenstr, lenpart,10 , 13);

printf("From %d matching.\n", s);

return 0;

}

The next blog is about the finite automaton string matching algorithm.

The links to the other two blog posts are as follows:

- SMA (2/3) Finite automaton string matching algorithm - ZhongUncle GitHub Pages

- SMA (3/3) KMP (Knuth–Morris–Pratt) string matching algorithm - ZhongUncle GitHub Pages

I hope these will help someone in need~