What’s the Difference Between Private-Use Networks and Link Local? What’s the Relationship Between Peer-to-Peer Wi-Fi and Wi-Fi Direct?

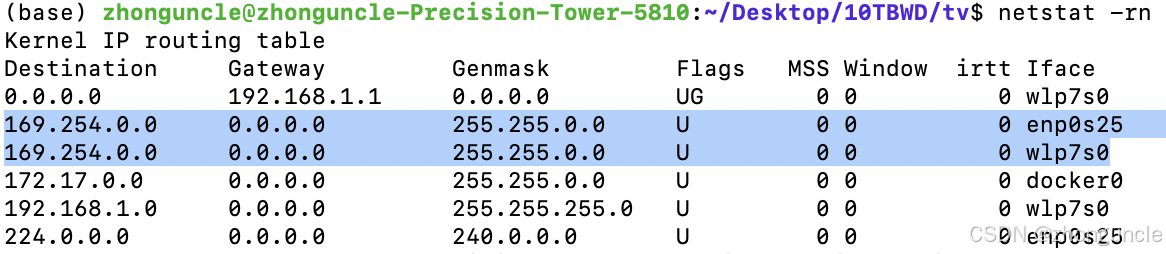

In my previous article Mac Suddenly Slow on Local Network (SMB, NFS, SCP, SSH, Ping, etc. Are All Slow), I mentioned that when checking the server with netstat -rn, the 169.254/16 IP block was mapped to two interfaces:

Why does this IP block correspond to two interfaces?

First, this entry is automatically generated by the system kernel. Even if you delete it, it will reappear after a restart. Therefore, I do not recommend modifying the routing table entries. Instead, adjust the subnet mask (or add a new entry, e.g., 169.254.0.0 with a mask of 255.255.255.0).

This raises the question: Why does the system generate such entries?

In the process of finding the answer, I gained an understanding of the difference between private-use networks and link local addresses, as well as the relationship between peer-to-peer Wi-Fi connection technology and Wi-Fi Direct.

Although we often say IP addresses are like “house numbers” that allow communication with specific devices, due to technical and legacy issues, IP address design is far more complex than simple “house numbers.”

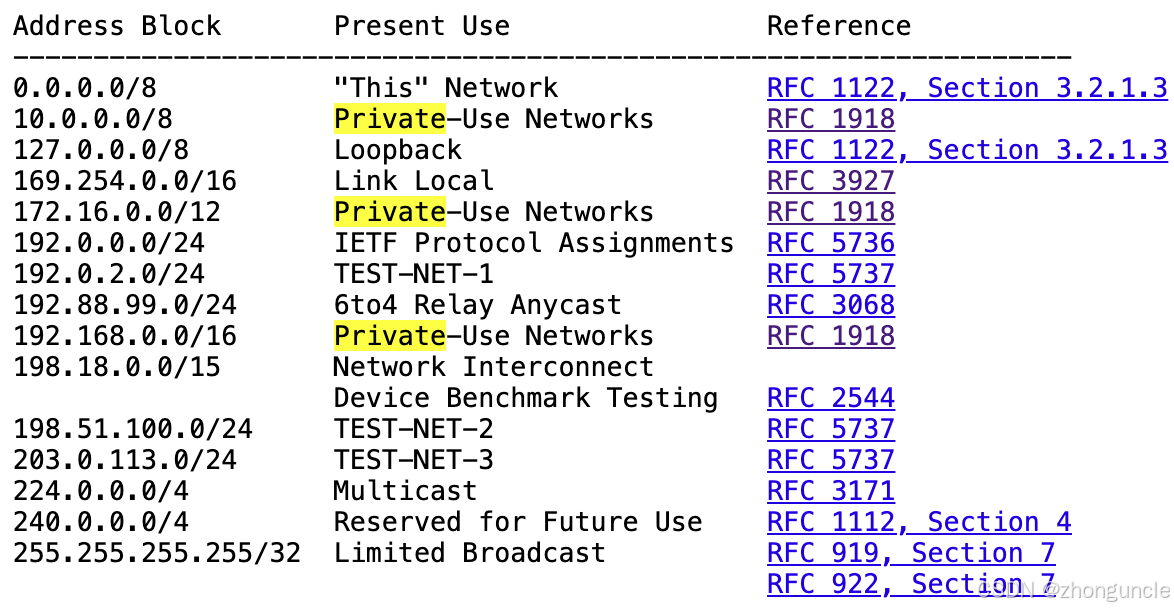

During the design of IP addresses, there are special address blocks. RFC5735 specifies some special IPv4 addresses:

As shown, 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, and 192.168.0.0/16 are the three reserved private-use network IP blocks, while 169.254.0.0/16 is classified as “Link Local.”

Private-Use Networks

Private-use networks were designed to extend the lifespan of IPv4. You’ve likely heard this description: Ideally, every device should have a unique IP address, but the proliferation of devices has exhausted available IPv4 addresses. Instead, a network can use one public IP address, with private addresses for internal devices—greatly reducing the number of public IPs needed.

For example, your home router has a public IP address (globally unique). It connects to devices like your phone, TV, washing machine, computer, and iPad. The router assigns private network IP addresses to these devices (usually via DHCP auto-assignment), typically starting with 192.168.x.x (or 192.168.1.x depending on the subnet mask). When you need to access external networks, the router/gateway establishes communication with devices on other networks. Converting private IPs to public IPs is done via NAT (Network Address Translation). When using private IPs, devices/routers automatically recognize them as internal and do not route traffic to the public internet. This is a simplified explanation— the technical implementation is far more complex.

A side note: 5GHz Wi-Fi can support more devices than 2.4GHz Wi-Fi. If you have many devices at home and some can’t connect to Wi-Fi, try connecting to the 5GHz network (my friend’s washing machine can’t connect to 2.4GHz—some devices limit connections to ensure quality).

RFC1918 provides a concise definition of private-use networks:

This document describes address allocation for private internets. This allocation allows full network layer connectivity among all hosts inside an enterprise as well as among all public hosts of different enterprises.

Link Local

As mentioned earlier, IP addresses for a network are usually assigned automatically (via DHCP) or manually. However, if no such configuration exists, the host assigns an IPv4 address from the 169.254/16 prefix to the interface. This address is used for communication with other devices connected to the same physical (point-to-point direct connection) or logical (switch) link. In other words, link local refers to “being on the same link.”

For example, in my previous article, a PC and Mac were connected via a switch without a router or other device to assign IP addresses. They used link local addresses to communicate, with no routing involved. Thus, RFC3927 refers to 169.254/16 as “non-routable addresses.”

I mentioned a similar phenomenon in Solution: Missing IPv4 Address on Ethernet (eth0) in Raspberry Pi 4B (Raspbian Bookworm): The RJ45 port had no IP address until set to “Link_Local Only.” Now we know the interface was waiting for the router’s DHCP to assign an IP address.

RFC3927 defines link local as follows:

Hosts are considered “on the same link” if and only if:

- When any host A in the group sends a packet (unicast, multicast, or broadcast) to any other host B in the group, the entire link-layer packet payload arrives unmodified;

- Broadcasts sent by any host in the group via this link are received by all other hosts in the group.

By now, you should understand why routers typically assign DHCP addresses starting with 192.168/16, while RJ45 ports without an Ethernet cable connection use addresses starting with 169.254/16.

Why Does 169.254/16 Map to Two Interfaces?

According to the definition of link local, Wi-Fi interfaces can also meet this requirement: Point-to-point Wi-Fi connections can be established directly without a router. Naturally, some systems assign a link local IP prefix to Wi-Fi interfaces as well.

The commonly used peer-to-peer Wi-Fi connection technology today is called “Wi-Fi Direct.”

Note: The technology itself is named “Wi-Fi Direct,” while such technologies are generally referred to as “peer-to-peer Wi-Fi.” Wi-Fi Direct is a type of peer-to-peer Wi-Fi—be careful not to confuse the two.

While not widely used in daily life (most Wi-Fi usage involves internet access or connecting devices like washing machines via routers), its application scenarios and support have expanded significantly.

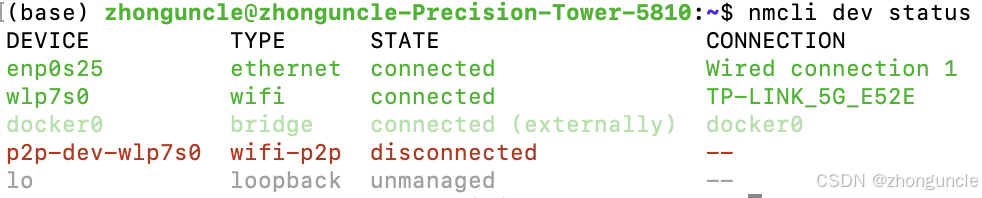

If you run nmcli dev status on Ubuntu 22.04 to check interface status, you’ll find a Wi-Fi interface of type wifi-p2p:

This confirms my earlier guess—we finally have the reason why the system automatically assigns the 169.254/16 prefix to both interfaces.

I hope these will help someone in need~

Wi-Fi Direct Across Platforms and Manufacturers

Below are introductions to Wi-Fi Direct usage across various platforms and manufacturers, demonstrating that this technology is not obscure.

You can exit this article now, as the following content is mostly introductory and extended—feel free to read on if interested.

Android

Android Development: Create Peer-to-Peer Connections with Wi-Fi Direct:

Android Phone Settings

Many Android phones include relevant settings. For example, OnePlus/OPPO devices call it “WLAN Direct”:

Additionally, OPPO’s explanation of What’s the Difference Between Wi-Fi Direct and Wi-Fi Tethering:

Samsung

Samsung’s Introduction to Wi-Fi Direct:

HP

HP’s Guide to Using Printers with Wi-Fi Direct:

Apple (Slightly Special)

Apple’s “AirDrop” uses a mix of networks, including Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and even the internet:

For example, AirDrop still works even when all Wi-Fi connections are disconnected and Bluetooth is turned off:

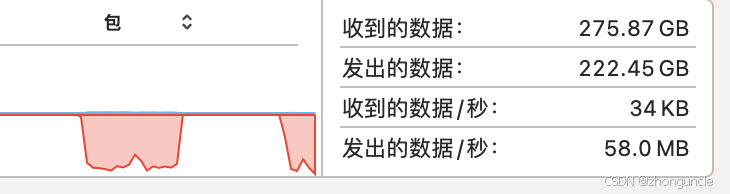

Its speed is slightly faster than when Bluetooth is enabled (48MB/s):

However, Apple’s Wi-Fi Direct implementation is unique: It is not one-to-one but m-to-n.

State of Apple’s “Wifi-Direct”, UDP connections, etc. - Apple Developer Forums provides a good description:

Apple’s peer-to-peer Wi-Fi allows N clients to communicate with M servers, just like regular Wi-Fi. For example, if two servers A and B register a service, and two clients C and D browse for services, C and D can see and communicate with both A and B.

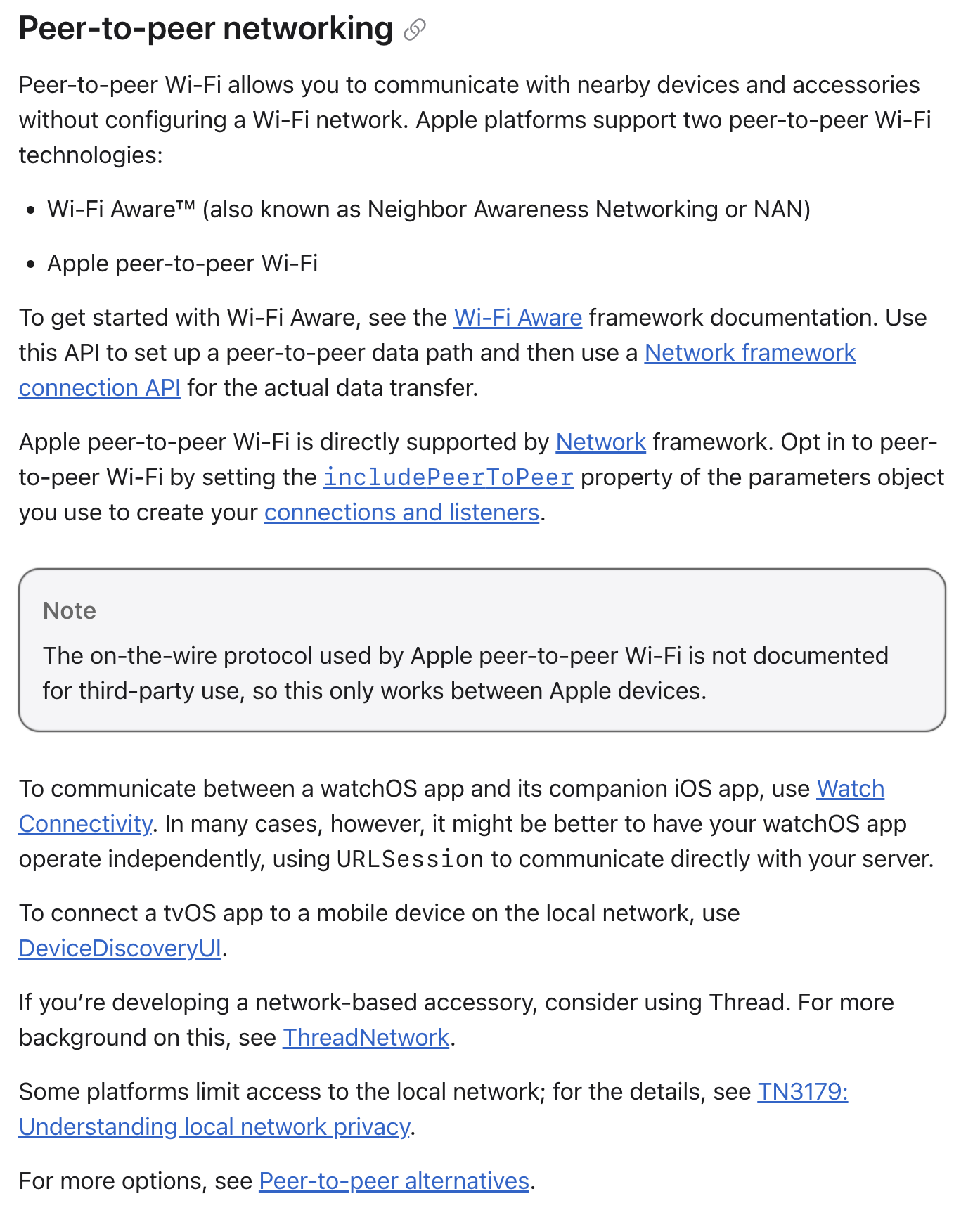

Apple’s official introduction to peer-to-peer networking in TN3151: Choosing the right networking API - Peer-to-peer networking:

The “peer-to-peer alternative” is the Multipeer Connectivity framework:

Further Reading

Many relevant resources have been linked throughout the article. Below are additional articles I found during my research that are not directly related but provide valuable insights.

P2P networking between Apple devices - Apple Developer Forums: A DTS Engineer provides useful information and explanations, such as:

Wi-Fi Fundamentals - Apple Developer Forums: A resource shared by the same DTS Engineer in the above thread, covering Wi-Fi-related technologies.

iOS and Wi-Fi Direct - Apple Developer Forums: Although this 2015 thread is older, the DTS Engineer’s responses are still helpful. For example, it mentions a solution similar to my earlier demonstration: